Before she was the first woman to be mayor of Rankin Inlet, Levinia Brown was a little girl forced into residential school.

Her mother taught her Inuktitut but she was forbidden to speak it there.

“I had no voice…. I was embarrassed a lot. ‘Look at Levinia, she can’t even sing, she can’t even speak.’ How could I speak when they took my language away?” says Brown.

She shared this from the podium during a gathering in which The Winnipeg Foundation announced a $5-million gift towards a new building for the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

“NCTR’s new home for Survivors brings us hope,” says Brown. “Hope for healing. Hope for reconciliation.”

It will be built at Southwood Circle on land gifted by the University of Manitoba, near the banks of the Red River. The facility is the vision of Survivors: a permanent home that will serve as an international learning lodge and a safe space for thousands of Survivors’ truths and statements.

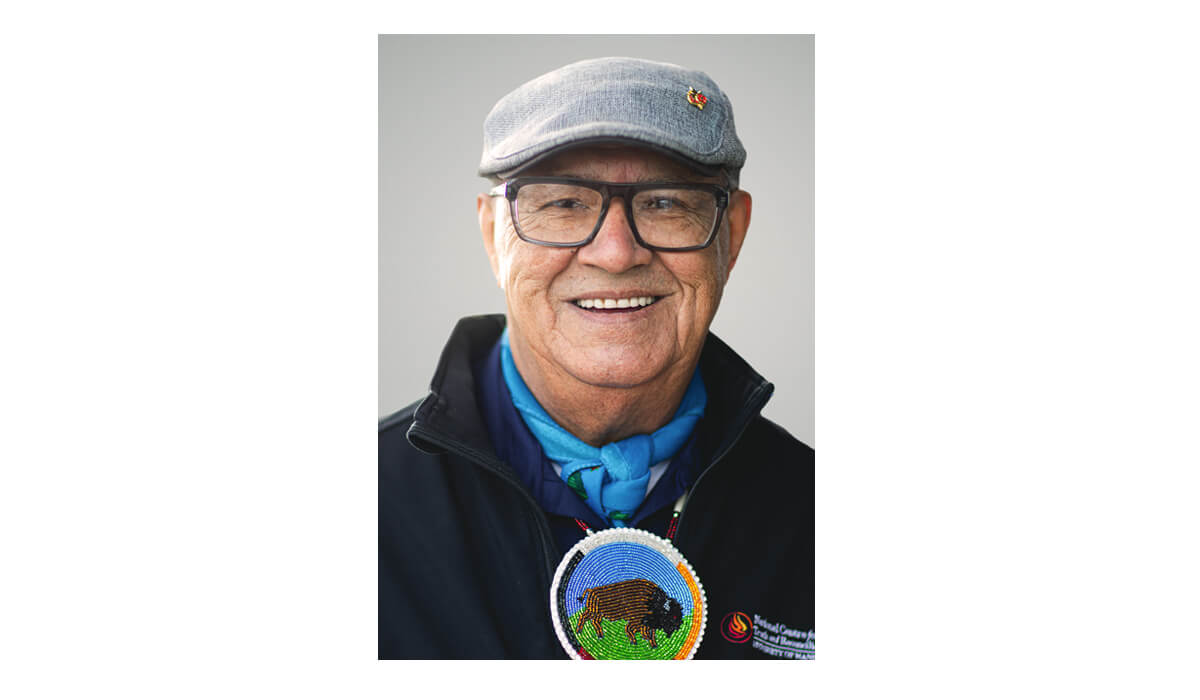

Residential school Survivor Eugene Arcand // Photo by Mike Latschislaw

From Muskeg Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan, Eugene Arcand says he was among the many Survivors who never learned how to parent and admits to being absent as a dad for 30-some years. Navigating emotion has been a journey. He spent 11 years in residential school.

“We didn’t learn how to cry until we were adults. We got punched, kicked, slapped, physically and psychologically, emotionally abused for most of our childhoods. And every time something happened we were told, ‘Don’t you cry.’”

Arcand reminded young parents in the room to let their babies cry if they needed to. When he welled up, seven Survivors, including Brown, rose from their seats and stood behind him at the podium in silent support.

“There aren’t very many of us left,” noted Arcand. “So while we’re here get to know us because we want to get to know you.”

The gathering for the gift announcement began with ceremony, followed by the procession of the memorial cloth // Photo by Mike Latschislaw

The memorial cloth, measuring 50 metres in length, is among the sacred items that will be protected in the new building. The cloth holds the names of thousands of children who never made it home from residential schools.

Elsie. Tommy. Violet. Dummy Bad Boy. Student 0131.

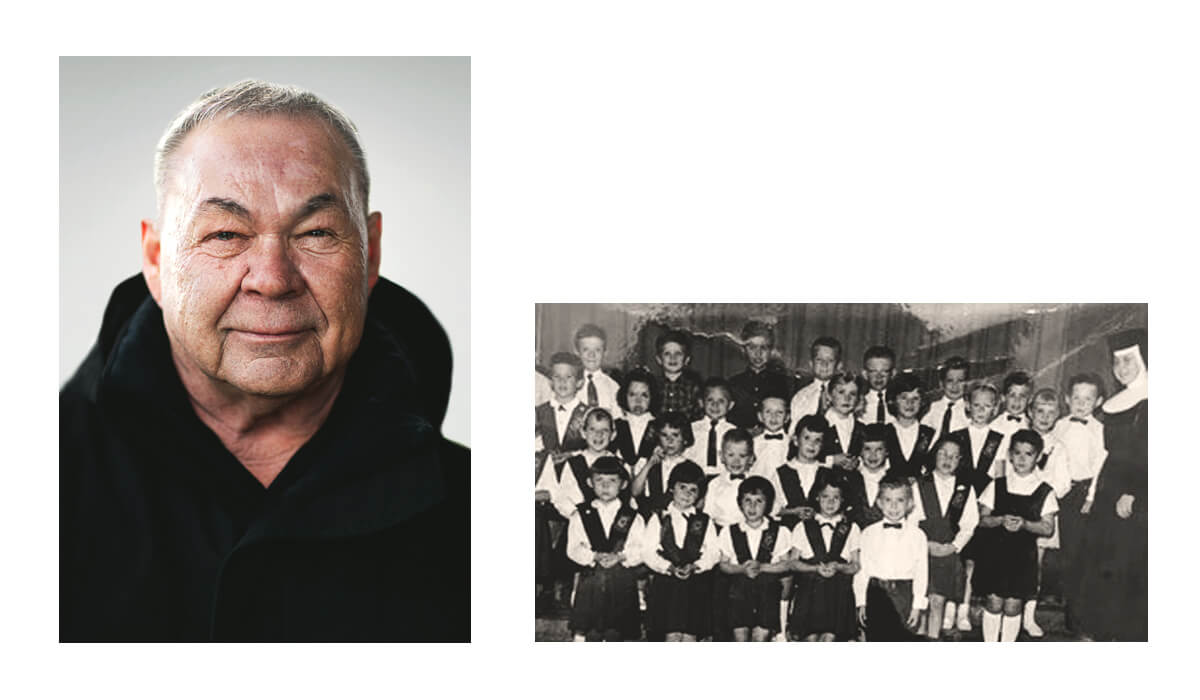

Brian Normand is a Métis Elder and Knowledge Keeper who was forced to leave his family at five years old to attend day school. Normand, now 66, says this forever home for the Centre will also be a home for the little ones who didn’t survive.

“I think about our missing children—and they’re dancing in the stars up there. They’re waiting to come home. This will be a home for them to come to as well.”

Brian Normand, of Métis/Michif descent, says his “spirit was broken” at St. Charles Day Residential School (back row, far right). He has since dedicated more than two decades to being a spiritual caregiver and Elder in Manitoba prisons // Photo of Normand by Mike Latschislaw; Class photo courtesy of Grass Roots News

‘It Must Never Happen Again’

The NCTR’s executive director Stephanie Scott also speaks from her heart when she shares her story. As an Indigenous woman, she has faced her share of discrimination. Notably when security officers in local stores have followed her around, suspicious she’s shoplifting.

“It’s demeaning. It’s paralyzing. It’s frustrating. It’s hard to be looked at differently, for somebody to see you as a visible Indigenous person and think that you’re less than—because I’m not. We’re not.”

Stephanie Scott, executive director of the NCTR, in their current location at Chancellor’s Hall on UM’s Fort Garry campus—a temporary space they’ve since outgrown // Photo by Rachael King

For Scott, a 60s Scoop Survivor and the daughter of a residential school Survivor, an investment in this building is about more than a physical structure. It sends an important message that other organizations, governments and individuals all have a role to play in reconciliation.

“I was moved to tears [at the announcement]. I’ve been doing this work for 14 years and no matter where I was in the country, the number one thing Survivors asked for was a place to protect, honour and preserve their history, their oral histories, for perpetuity so that what happened to them as the most vulnerable young children can never happen again in our society.”

She has heard many heartbreaking truths from Survivors firsthand. One grandmother shared with her how, as a young child, she was the one to care for a fevered classmate in their dorm with no adults willing “to hold her and love her and make sure she’s safe.” She recalled holding her friend as her body suddenly gave out and became lifeless.

Scott feels the pain of these stories and the weight of heavy responsibility. But says she’s never done this work alone.

She is grateful for committed staff, the ongoing guidance from the Survivors Circle and the Governing Circle, and for the support from the University of Manitoba. It’s a mission she’s eager to see to its full fruition, as there are fewer Survivors with every year that passes.

A New Home

The $100-million facility is projected to open in 2029. Currently, sacred items and offerings are scattered across campus and stored elsewhere in Winnipeg as they require humidity-controlled conditions. The ultimate goal is to have them proudly on display, showcasing Indigenous history, culture and the teachings of spiritual practices.

And while many of the millions of Survivors records have been captured digitally, it is crucial that physical records have a home, says Scott. A home where Survivors, their families and communities can access their histories. A place where they can look through historical residential school photos, potentially furthering the identification of children who died in those institutions.

“The NCTR’s new building will be a beacon for reconciliation in Canada—a place of learning and dialogue where Survivors’ experiences will be honoured and kept safe for future generations,” says Scott. “A safe place, a home to help Survivors with their healing journeys. And a dedicated space where guests from Canada and around the world can visit to learn about the residential school experience and our collective history.”

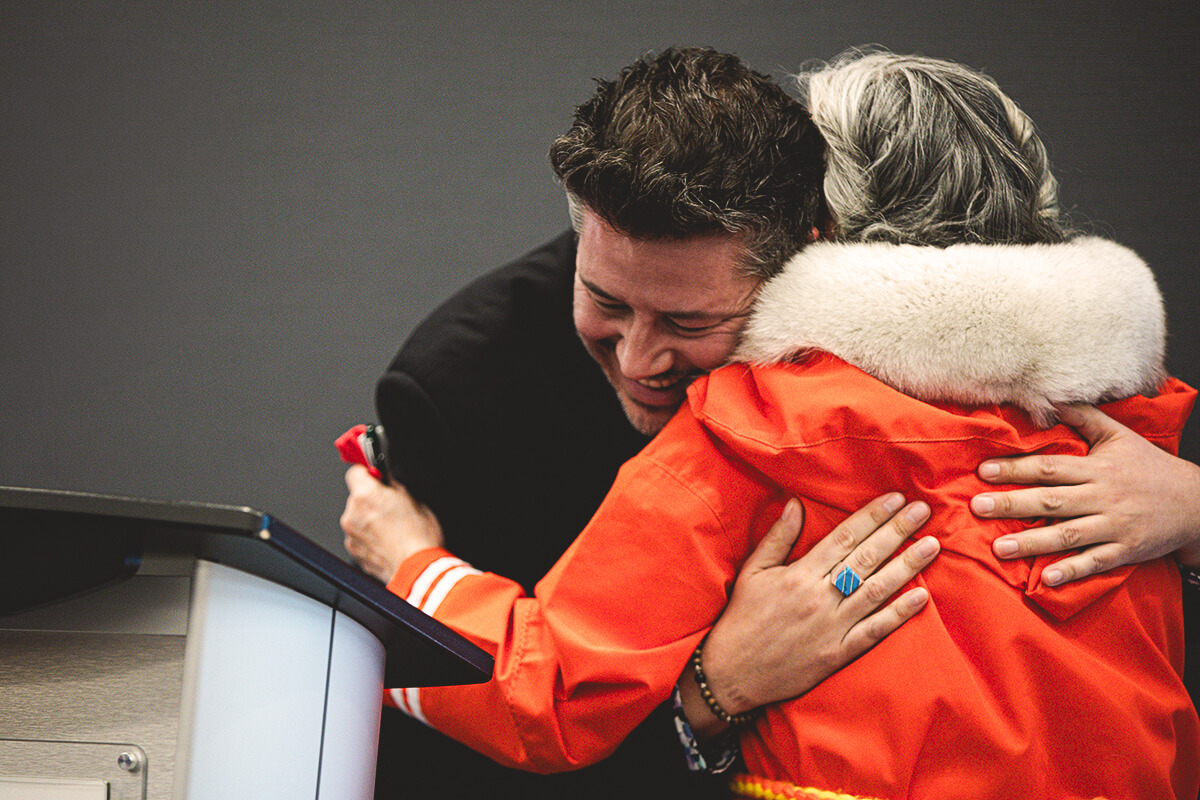

Sky Bridges of The Winnipeg Foundation hugs residential school Survivor Levinia Brown at the March 14 announcement of their gift // Photo by Mike Latschislaw

A Call to Action

The Winnipeg Foundation’s gift to the NCTR is the largest single grant to an Indigenous-led organization in its more than 100-year history. Philanthropy, as president and CEO Sky Bridges sees it, is about loving someone you don’t know.

“It’s incredible to think that this grant—the $5 million—is a gift from thousands of hearts from the past to help make a better future.”

Bridges offered a message to Survivors: “I want you to know that you are loved. This gift represents love.”

With the federal government pledging $60 million, there’s another $35 million still to raise. UM President Michael Benarroch called on governments across the country to step up, along with Canadians from coast to coast to coast, given that reconciliation doesn’t end when a target fundraising goal is met or when a building opens.

Bridges hopes the Foundation’s gift will inspire additional donations.

“We hope that other donors will also make a gift and investment for this nation’s path ahead in truth and reconciliation.”

Learn more on the NCTR’s website about the plans for their new home and how you can support it.

Truth is wonderful. There is so little of it. Very precious. Like to see more truth.