![Illustrations by Jane Heinrichs [BA/05]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Avi_sketch_online-150x150.png)

Avi Slama [BCOMM(HONS)/87]

Tel Aviv, Israel (pop: 432,892)

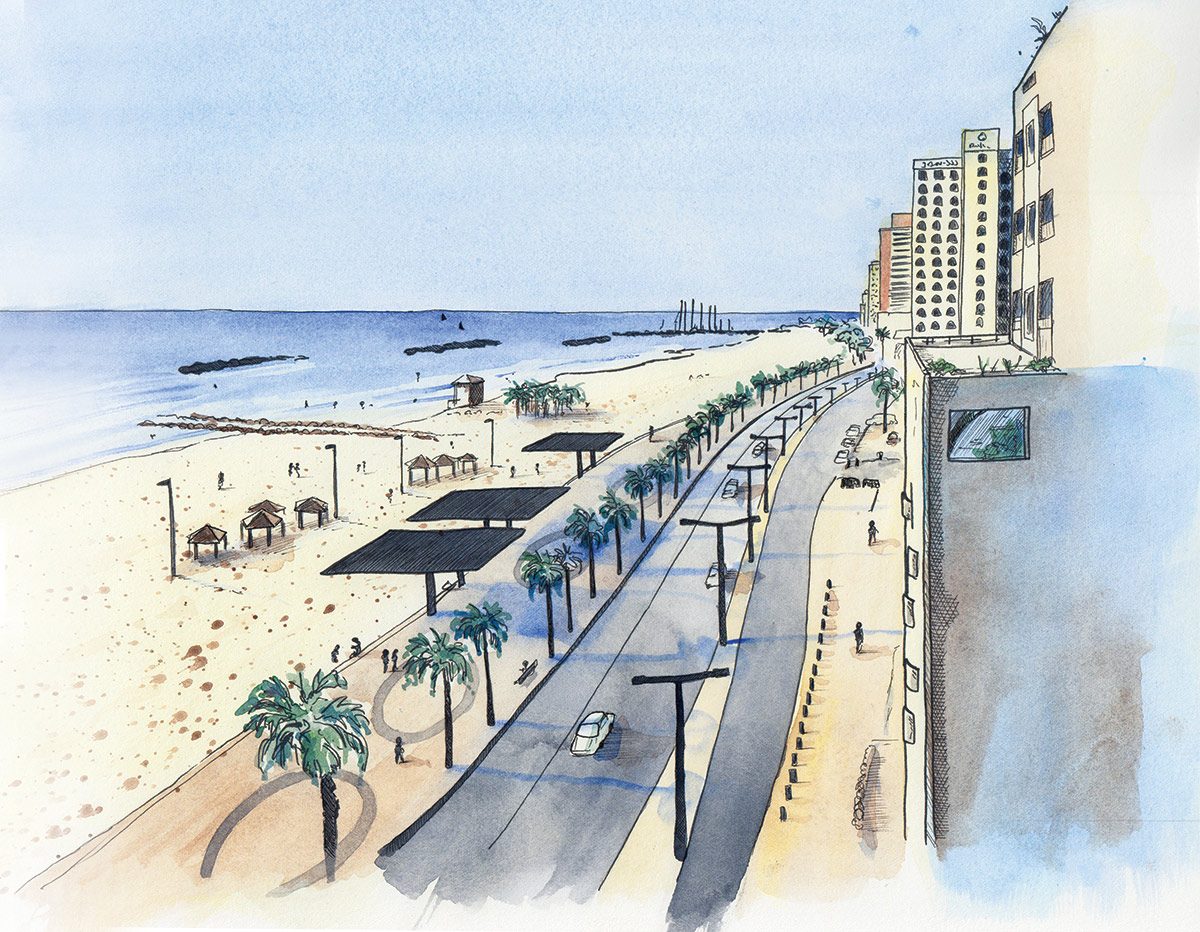

He owns an apartment, hostel and hotel in Israel’s second largest city and for more than two decades ran a popular 1,200-seat beach restaurant—called La Mer—on its Mediterranean coastline. Avi grew up there and after serving in the Israel Defense Forces, went exploring in Canada. He studied accounting, met his wife, and started a family in his new home before finding his way back to what’s known as the Miami of the Middle East.

You know, there is a lot of energy in Tel Aviv. There is young energy. I don’t know how to explain it. It’s special. It’s different.

I’m more like a fish in the sea, living here.

A lot of people like to travel after serving in the army, to get some air—some space—so I came to Canada. I landed in Montreal. It was December. It was frozen so I went back to the airport and found out Vancouver was the warmer place and moved there the next day.

I started to work and travel [across Canada]. I bought myself a little truck and I would stop in every town and city. It was just to feel the freedom. To answer to nothing. I ended up in Winnipeg.

The U of M is where I met my wife; she was in political sciences. I had to work while going to school. One of my jobs was a teacher’s assistant in Judaic Studies. A girl came to me and wanted me to help her with one of the topics. There were study halls—I used to go on Sundays to study. I told her I would be there and I would help her. [She] and her friend came in, and the friend was my wife.

When my wife finished her Bachelor of Law in Windsor, I remember seeing a nature program on the television about the Judaean Mountains. I saw the light and the sun and I said to her, “I have to go back.”

I used to have a big beach restaurant—it was fun. Like with every business, you need luck and to like what you do.

I’m very much into Jewish mystical wisdom, that everything is deterministic. I’m guided by God or this universe and just whatever happens will happen and just let it be. We are just a little boat in the sea and we go where the sea wants us to go.

I really believe that every bad thing you go through, it’s for a very good reason, and as you get older, you realize that more and more. You can see things from a higher point of view.

Some people need a lot of attention, and some people don’t. I’m the don’t. I guess I had good attention from my mom when I was young. She gave us everything she had, which was not much, but it was all she had.

My father was a butcher in a meat store, and then he worked at a textile factory. I grew up in a town up north, Qiryat Shmona, and we would hear rockets all the time. When you see rockets in the night, you think the lights are coming to you. There was a lot of conflict, but this is part of the story here. This is part of life.

I don’t spend too much energy or time on this now. There is less conflict here in Tel Aviv; if you want conflict, go to Jerusalem. And unfortunately it’s now spreading to Europe and elsewhere… This is the way it is, and that’s it, accept it. It’s not a major thing in my life. It happens.

In the future people will slowly realize that people don’t care much about all this conflict and then peace will happen. The media and the connectivity of everybody will all help stop the nonsense. I really believe that it will happen, but it’s not time yet.

![Illustrations by Jane Heinrichs [BA/05]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Jane_sketch_online-150x150.png)

Jane Heinrichs [BA/05]

London, England (pop: 8.7 million)

She moved to London from Winnipeg more than a decade ago to pursue a master’s degree in art history at the Courtauld Institute of Art, and is now an award-winning illustrator of children’s books. In the Mattie’s Magical Animal Dreamworld series, Jane brings to life characters that soar with the owls and walk tightropes with rhinos.

I love the history and grandeur of London. I love the lazy, verdant parks filled with towering sycamore and oak trees. I love the museums and the rose gardens. I don’t mind the rain, but the winter darkness is sometimes difficult.

I was safely at home when both the Westminster and Borough Market terrorist attacks happened. My husband works near Westminster, so he was closer. I wasn’t in London for the bombings [in the Underground] in July 2005, but I arrived a month later, and my student flat was a two-minute walk from Russell Square, where most of the damage was. Police were still working to clean things up while I was moving in. One always has the knowledge that something could happen in one’s subconscious, but life goes on, and one must forge forwards.

I do my drawings in my studio, a tiny room off our bedroom. It has a large, bright window, a tilting-top studio table, and a tall bookshelf filled with inspiring books and reference materials. At the bottom I have large exhibition catalogues from art galleries around the world. Above that I have novels and creative writing memoirs organized by colour—my mind is a rainbow.

Everything starts with a messy pencil sketch. Sometimes it’s so scribbly that it’s only legible to me. Then I work it up and add details. Once I’m happy, I’ll trace it onto thick, hot-press watercolour paper with my lightbox. I add ink lines with a selection of fine-liners and Japanese brush pens. Then I paint with watercolour.

When I was doing my BA at the U of M, I did a major in art history and a minor in classics. I worked as a research assistant in the classics department. They needed someone to draw reconstructions of various finds from their archaeological digs, so they asked me if I knew anyone in Fine Arts who would be interested. I said I would be happy to audition for the job. After that, my job description changed drastically from photocopying and library-runs to illustration. I loved distilling pages and pages of information about an ancient Roman statue, villa or kiln into one drawing. It was a form of storytelling.

I drew pottery sherds (or fragments) 95 per cent of the time, or skeletons in Roman burials. I loved it when I could do the rare villa or classical statuary reconstruction. Most of the drawing was done at home using dig photos and sketches as references. I did go on the U of M dig in Tunisia two years in a row, where I was able to draw pottery sherds in situ. It was amazing to feel the ceramics with my hands and really get to know the curves and undulations I was so used to drawing from photographs. Also, we would find the occasional ancient Roman fingerprint impressed into the clay. Those were inspiring moments.

It seemed natural to move from there into children’s books. But, mind you, it wasn’t an easy transition. It took years of rejections and perseverance. Children’s illustration is a very competitive field. Every year there are more and more illustration or fine arts graduates submitting their portfolios to publishing houses or agents. Editors call submissions the “slush pile.”

As a child, I was rarely seen without my nose in a book. I love the deft ink lines in vintage book illustrations, and I try to replicate that feeling with a modern edge.

Many of my friends are both creatives and mothers. So, we discuss the balancing act. It’s like being in the circus and trying to walk the trapeze with a baby on one hip and a notebook or sketchbook on the other.

The last sketch I drew was of myself running errands in Kingston upon Thames. I try to do a drawing a day, and many of them are like one-image autobiographical comics. I started doing them after my daughter was born. I was desperate for a creative project that was small, daily and cumulative, to keep me from feeling too isolated.

Olaf Juergensen [MA/89]

Istanbul, Turkey (pop: 14.8 million)

Olaf works for the United Nations Development Program, which has experts stationed around the world to tackle major global concerns like climate change, gender inequality and poverty (where he comes in). He navigates the rubble of war, coordinating efforts in the aftermath of conflict to remove landmines blocking the way of communities in places like Angola and Zimbabwe as they try to rebuild.

I travel quite a bit. Probably two weeks of every month I’m gone.

Istanbul is awesome because I can be in Moscow in five hours. I can be anywhere in Europe in two to three hours, and it’s only 45 minutes to Lebanon.

I just did seven trips in six weeks.

To find mines that target people (called antipersonnel landmines), you use a detector or you can use dogs. They’re usually only about 10 to 15 centimetres underground, otherwise the weight of the person won’t set them off.

The victims tend to be younger people. If you’re a teenager and you step on a mine, it’s not just you that has to recover, but your whole family is going to be involved in supporting you for years to come.

We try to give them skills and opportunities to live in dignity. If someone has lost their arm, their foot, their eyes, you can teach them a basic skill—how to weld, how to sew.

Clusters are bombs typically dropped from the air, and just before they hit the ground, the bomb opens and hundreds of little bomblets come out. These things are a little bigger than a tennis ball and very imprecise. They are set to go off in mid-air after a certain amount of rotations. Up to 25 per cent of them don’t go off as they should. The danger is you could pick it up and move it seven times and nothing, or move it an inch and it explodes.

The worst part is they often have these little parachutes as they float down; sometimes they get stuck in trees. A parachute with a little bomb on it—how inviting is that for a kid? There are millions and millions of these things, spread mostly across Asia and the Middle East. It’s really sad and abhorrent.

Because of extreme poverty, some people try to take the explosives out, harvest them, and sell the metal. Imagine cutting through a bomb.

It’s not uncommon to have to walk through mine fields to collect firewood, reach water or buy clothes and food.

The number of victims is going up mostly because of the conflicts in Iraq and Syria, because these are really arduous ones. We haven’t seen war like this in a long time.

The physical damage—the scars of war—are truly complicated in countries that are developing to begin with. When the infrastructure is damaged, the country doesn’t have the resources to fix it. The telecommunications, the hydro systems are the first things that are attacked. Also the road networks, which are critical for not only economical reasons but for tying together countries and building social cohesion.

Is world peace possible? I would like to think so. That would be an ideal or a vision of mine, of everyone’s—of John Lennon’s. But unfortunately, in the complex world we live in, with the competing agendas, and when we have strong states and weak states, you have issues. With the gulf between rich and poor between countries and within countries, people are being left behind. It’s inequality that needs to be resolved. You just have to look to the U.S. and the inequality around health care, race, class and so on—unless that is sorted out, we’re not going to have peace.

You don’t have to have something drop on your head to not be in peace. You might be abused, there’s human trafficking, you might be enslaved in the 21st century.

My parents emigrated from Germany. My grandfather was killed in the Second World War. My parents were teenagers when it ended. They grew up with bombs raining down on them, through no fault of their own. It was the adults making the problems, not the kids. They were just kids.

I remember this real melting pot in the geography department at the U of M. It was really on the cutting-edge of international development work. We worked on floods and population growth in Bangladesh. That’s what got me interested in doing international work. There were seven or eight PhD students from Africa and Bangladesh. We used to all eat together, trying different traditional foods. We’d sit on the floor, eat with our hands, chicken and fish with curry. It gave me a sense of where they were from, what their lives were about.

I tell my kids to look around. To do something interesting, yes, but also to do something that is meaningful to others. They grew up overseas and understand the world is a big place.