In the back bedroom of their bungalow in Churchill, Man., Antonina Kandiurin’s proud parents share a laugh over her unique decor choices over the years, including the painted polka-dot walls.

“Oh my God, I’ll never do that again,” dad Dmytri Kandiurin says with a smile. “It took 10 coats to cover the black polka dots.”

It’s been several weeks since 24-year-old Antonina [BKin/23] left her childhood home, near the coast of Hudson Bay, to start med school at the University of Manitoba. Her plan? Make her mark in northern medicine. Antonina wants to one day return to this remote town of fewer than 900 people to work as a physician.

Graduating more Indigenous doctors is among the many goals of Ongomiizwin – Indigenous Institute of Health and Healing. This University of Manitoba network is the largest Indigenous education and health unit in Canada.

It is through Ongomiizwin (an Anishinaabe word that means “clearing a path for generations to come”) that physicians travel to rural and northern regions across Manitoba and into Nunavut. These health services build on the J.A. Hildes Northern Medical Unit, launched at UM in 1970 by Dr. John Arthur Hildes, a professor and early advocate for health equity for people of the north.

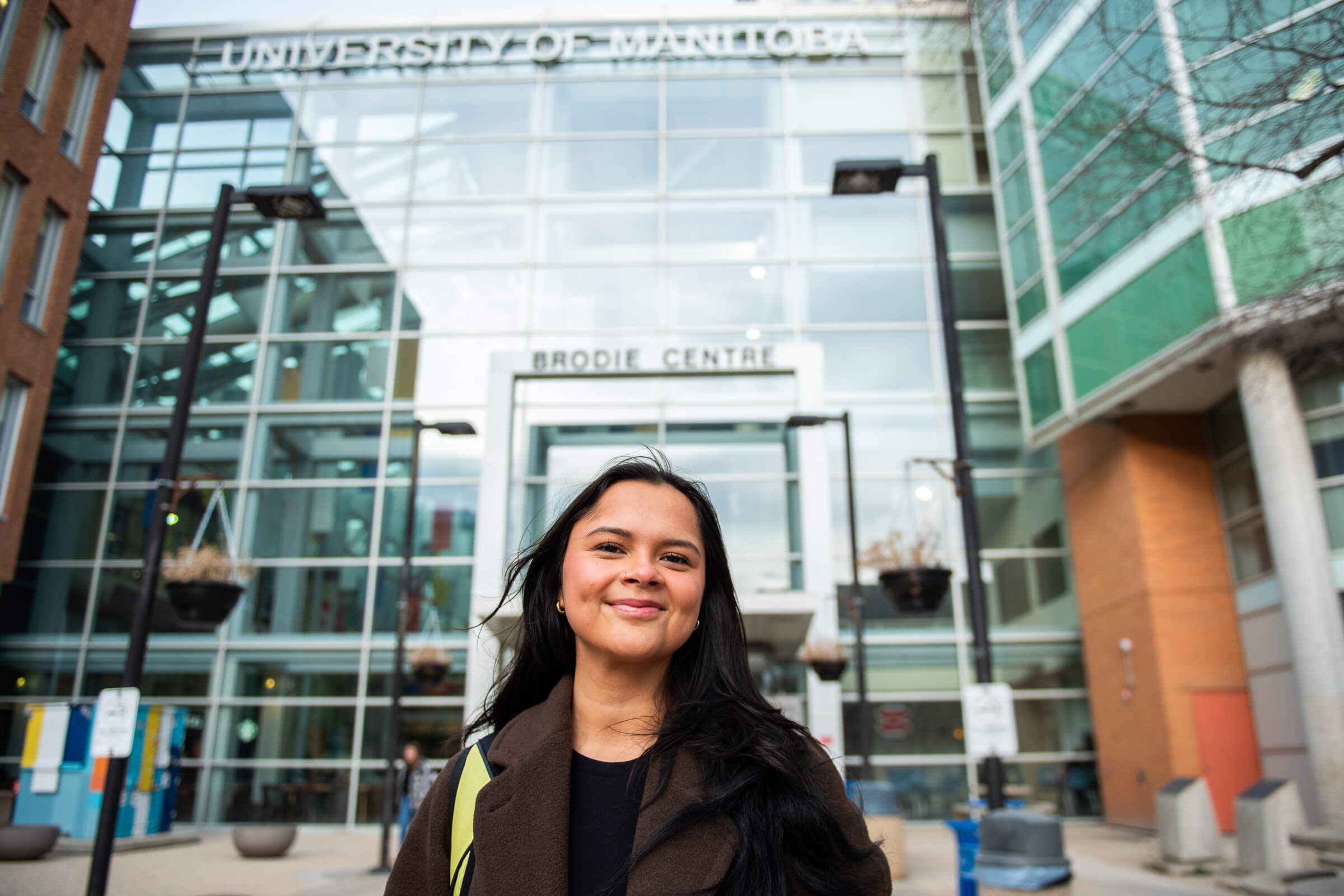

Antonina Kandiurin, on the Bannatyne campus, after finishing an exam. Her Winnipeg roommate is a fellow aspiring doctor from Norway House

Dr. Justin Bender [MD/11] has been flying into “the polar bear capital of the world” for 11 years now. Here, Bender doubles as a family physician and an ER doc for two-week stints. He also travels to the northern regions of Kisipakakamak (Brochet), a Cree community of about 60 people on Reindeer Lake; Dahlu T’ua (Lac Brochet), a Dene community, also on Manitoba’s western edge; and Tes-He-Olie (Tadoule Lake), west of Churchill and home to Sayisi Dene First Nation.

Saskatchewan-born Justin Bender moved to Manitoba to enroll at UM and did the northern-remote family medicine residency program, designed to address ongoing issues of doctor shortages

In recent years, the hours that physicians spend in these fly-in communities has tripled through Ongomiizwin Health Services. Residents can now see a doctor in person for two days out of every 14. On the other days they have access to nursing stations, which can consult from afar with the doctor on duty in Churchill.

It’s a significant improvement in accessible health care in Manitoba’s north but there is still a ways to go, Bender says. The weekend before, a patient arrived from further north, requiring intubation before carrying on to Winnipeg for further care.

“It’s basically a matter of funding. We make that work, but it’s not really what should be the standard of care for someone who’s a Manitoban,” Bender says. “I would say 85 to 90 per cent of patients seen at a nursing station are dealt with by the nurses there who have an extended scope of practice and a lot more independence. But they’re also worked pretty ragged sometimes.”

Learning as a settler

Ongomiizwin leads the implementation of the Rady Faculty of Health Science’s Reconciliation Action Plan, developed in response to the health-related calls to action made by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. For its Indigenous and non-Indigenous physicians, the Institute emphasizes the importance of listening, learning, being compassionate, accountable and respectful.

Bender says, “The patients, as they trust you and open to you, they teach you. They teach you how to help them and how to live your life better too. It wasn’t something I was quite expecting, but it’s been wonderful.”

Oftentimes his patients are dealing with multi-generational trauma and poverty.

“That just makes it very, very difficult for people to find a way to move forward,” he says.

It’s not an experience Bender grew up with.

“This inhibits so much of people’s lives in a way that, as a settler, is really hard for me to directly interface with and so it’s something that becomes learned with time.”

ALL VIDEO BY MARK NEUFELD

Bender appreciates it when the hospital’s Indigenous Healer, a recent addition, brings attention to ways the team can offer more culturally safe care. In the last few years, the hospital began supporting a Warrior Caregiver land-based wellness program for Churchill men who meet regularly for group activities, like AA “wellbriety” meetings and cooking classes.

Access to traditional foods is part of a more holistic conversation Bender has with patients with diabetes, hypertension or heart disease. “The absence of these foods could be a direct cause of a lot of the pathology that we see,” he says.

And Bender has witnessed how chronic under-access to specialized health care creates apathy over time.

“People get pretty used to not having that access and so they just kind of lose a certain amount of hope and maybe they wait too long to come in because they’re used to long waits or not having access or being ignored,” says Bender. “It’s one of those things that, oftentimes, the patient gets blamed for it. But it’s a systemic issue.”

Simionie Sammurtok, Mayor of Chesterfeld Inlet in Nunavut, had a stroke in 2007 and regularly travels to Winnipeg for medical care. A physician flies into his community only every three months and, with a shortage of nurses, the local health centre is sometimes only open for emergencies. “It’s really hard,” says Sammurtok

Leaving the community for care

The range of specialists Ongomiizwin deploys to communities has expanded nearly four-fold from its original six, with a growing list of services like obstetrics, occupational therapy and geriatric medicine. They also bring diabetic foot care and retinal screening programs to First Nations communities in Manitoba. In Churchill, the fly-in specialists include a rheumatologist, an internal medicine doc, a urologist and an ear, nose and throat doc, among others.

Patricia says she dreads going south for care when a specialty is not available at home. She found herself alone with appendicitis in the emergency room in a Winnipeg hospital, worried she’d be discriminated against. One of Ongomiizwin’s priorities is to educate all Rady Faculty of Health Sciences students and faculty members in anti-racism.

“I’m sitting there all by myself and I was kind of scared so I moved closer to the security guard,” says Patricia, “and I had to explain myself so I wouldn’t be considered a drunk Indigenous person in emergency. I said, ‘I’m from the North. I’m a diabetic and I have appendicitis.’ I don’t want a security guard thinking that I’m drunk because I may have low blood sugar. He says, ‘I’ll watch you. You just stay close and I’ll watch you.’”

She’s hopeful her daughter’s generation will help to combat discrimination in health care.

Logistics challenges and risks in the north

Dr. Erika Pearce, a nurse-turned-doctor who sees patients in Churchill and other fly-in sites, says specialist visits to Winnipeg are no small endeavour, especially if patients aren’t covered under Treaty Services and must pay their own expenses beyond travel.

“Just going to the city for a lot of people from the north is overwhelming,” says Pearce.

There can be a lack of understanding of these added hurdles when coordinating out-of-community appointments for her patients.

“They’re not realizing that this means somebody may have to leave their community a few days before their appointment, and not be able to get home for a few days after their appointment. And that it could be weather dependent. They may have kids at home or elderly parents that they need to find somebody to look after and there isn’t respite. They don’t rely on their phones the same way we do in the south, so with the cancelling of appointments and that sort of thing the expectation is different, too,” says Pearce.

Given the challenges of being so remote, Pearce says extra thought goes into whether they send patients out for further tests—like a CT-scan—since Churchill has only X-Ray and bedside ultrasound.

“The risks and the benefits are different here in the north,” says Pearce. “The advantage that we do have is: because we’re a small community and a small group of physicians, I can see somebody in the nursing station overnight, or in the hospital in Churchill overnight, and I can treat them and then have them come back for follow-up the next day, or within a few days, to make sure they continue to improve. You can’t do that in a place that’s completely overwhelmed.”

She’s optimistic as more specialists expand coverage across Manitoba, like the recent addition of an obstetrician-gynecologist serving Red Sucker Lake First Nation in northeastern Manitoba—where she also flies to.

Patricia says having a dialysis machine in Churchill would be a gamechanger for locals who need it. Expectant moms must also travel south in advance of giving birth. She had to spend two weeks away from home when having Antonina, who would become the first in her family to get a university degree when she earned her undergrad in athletic therapy in 2023.

Growing up, Antonina says she didn’t see doctors who looked like her. And she didn’t feel listened to, especially following her diagnosis with type 2 diabetes at 16 years old.

“There was a lot of blame associated with that. I had to really fight for myself to get proper treatment and for my doctors to actually listen to me when I told them that the treatment that I was receiving wasn’t working,” she says. “I think it just stems from this generalization and stigmatization of treating patients from the north, and also Indigenous patients, that I just wasn’t trying, which was not the case.”

Antonina says during her second year of her undergrad she almost gave up. The curriculum felt too challenging and the calibre of education she received in her community didn’t prepare her for it.

“But I pushed through,” she says.

Students around her didn’t seem aware of the challenges she and others grew up with, which can weigh on mental health. When Antonina heard that two girls from York Factory First Nation and Tataskweyak Cree Nation, ages 13 and 14—friends of her cousin’s—took their own lives, she pledged to raise awareness. She ran every day for a month at UM, to bring this dialogue to campus.

“People didn’t know. And because they didn’t know, they didn’t care.”

It was a proud moment when the Bisons women’s basketball team—whom she treated as their athletic trainer all season—joined in.

“Being a youth that grew up in an isolated community, I understand how it can feel when you can’t visibly see what could become a reality. Your dreams honestly seem fake sometimes. And I wanted [teens back home] to know that they could be capable of anything in this world they want to do. And that there is a reason to live and to keep going.”

After graduating Antonina came back to Churchill and led a women’s holistic wellness group at the hospital, creating access to sweat lodges and full moon ceremonies.

“It was a really grounding and reconnecting experience for myself too, being able to reconnect with my home and my family and my culture, especially after being away for six years in my undergrad. It was very healing for me.”

Antonina counts Bender and Pearce among her biggest cheerleaders.

Her goal as a doctor is for her patients to feel at ease when they come see her. “That they don’t carry any fear or past traumas with them from the health-care system. And to know that I am a safe person and there is not going to be any bias towards them based on their culture or their identity,” says Antonina.

“I want people to know that health care is a basic right and they shouldn’t be scared trying to access it.”

I loved this story. So much hope and promise here..

I want to be part of it

Guide me

I was touched by this story. I graduated medical school in Wpg in 1971, and Dr Hildes was just starting his program. He taught about what we now call cultural awareness and it left an

Impression on me.

Although I practiced psychiatry for almost 40 years in a large American city, I believe much of what I learned then translated into how I treated minorities here! Good for U of M

This is a great article. I lived in Churchill for 12 years in the Late 70’s and 80’s. The people definitely require more care in the Northern area of our Province.

Best of luck to all the students who choose to contribute to the communities in the north,.

Bless you and thank you from my heart.

Congratulations Antonina in pursuing your dream. You have gathered much wisdom through your life and will be an amazing doctor for your people.