Test Your Knowledge of 140 Years of UM Medicine

Rewind to 1883. Western Canada’s fist medical school opened its doors with its inaugural class of aspiring physicians. As the Max Rady College of Medicine—once the Manitoba Medical College—celebrates 140 years, test how well you know its past and present, from alumni with big ideas to groundbreaking discoveries.

It was research into human physiology—specifically, how we adapt to cold temperatures—that first brought Dr. John Arthur (Jack) Hildes to the North. During his travels he witnessed the challenges in remote regions and became an early advocate for improved health care for Indigenous communities.

Hildes’ longtime commitment to the health and well-being of the people of the North would inspire numerous other physicians and researchers to carry on this legacy of care.

The J. A. Hildes Northern Medical Unit has since evolved into Ongomiizwin – Health Services. The team provides equitable access to health services for First Nation, Inuit, and Métis, with an emphasis on respecting Indigenous self-determination. They offer a range of services, from family practice to social work to rehabilitation therapy.

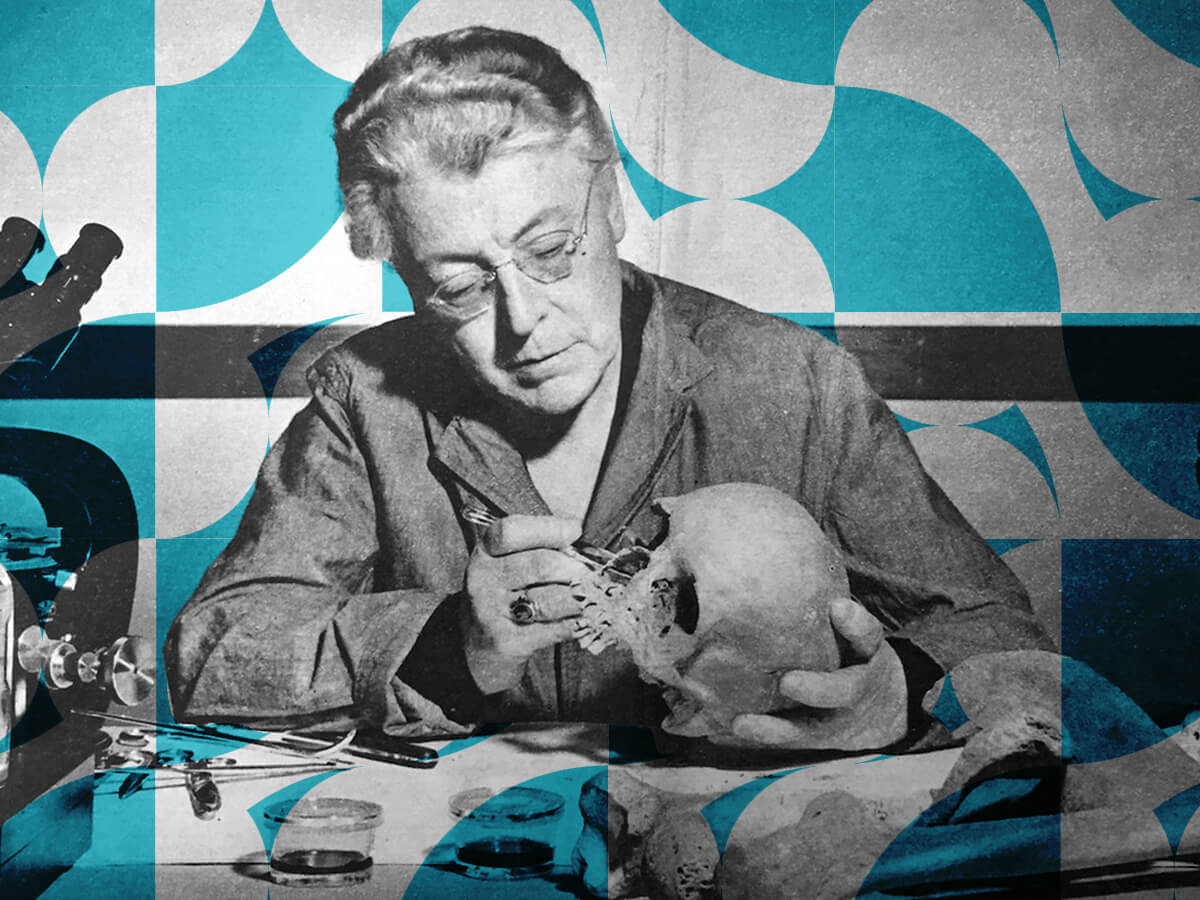

Frances Gertrude McGill / University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections / National Film Board

Dr. Frances Gertrude McGill [MD/1915], who graduated from UM more than a century ago, gained widespread fame for her role in developing forensic pathology in Canada. She was among the first female members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and helped establish their first forensic laboratory.

Shortly after completing her degree, McGill moved to Saskatchewan to become the provincial bacteriologist and later, provincial pathologist. For three decades she worked with the RCMP, teaching forensic detection methods to new officers. McGill continued to act as a consultant until her death in 1959.

Manitoba now has a centralized, medical examiner death investigation system and boasts one of the largest autopsy services in Canada, conducting more than 1,800 post-mortem examinations last year. Due to the high volume of cases in Manitoba, UM’s department of pathology offers a specialty residency training in forensic pathology where residents can gain experience in hospital autopsies and neuropathology consultation services.

In 2008, UM created the Centre for Global Public Health, building on its leadership in the field. Seven years later researchers travelled to Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, to join efforts to improve maternal and newborn health. The team systematically mapped gaps in the availability of facilities providing maternal and newborn care and worked with the regional government to improve access. Prior to this program, only about 50 per cent of pregnant women there were being seen by skilled medical professionals.

The research, led by what is now the Institute for Global Public Health and supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, also focuses on improving the availability of medical specialists, essential drugs and equipment to boost emergency care and save lives in more specialized centres.

Today, the majority of women are delivering babies in proper facilities. “We’re there as partners to do things together and to learn together,” says Dr. James Blanchard [BSc(Med)/86, MD/86], the Centre’s director and a Canada Research Chair in Epidemiology and Global Public Health. “The most gratifying part is seeing the ideas we create with our partnerships make an impact.”

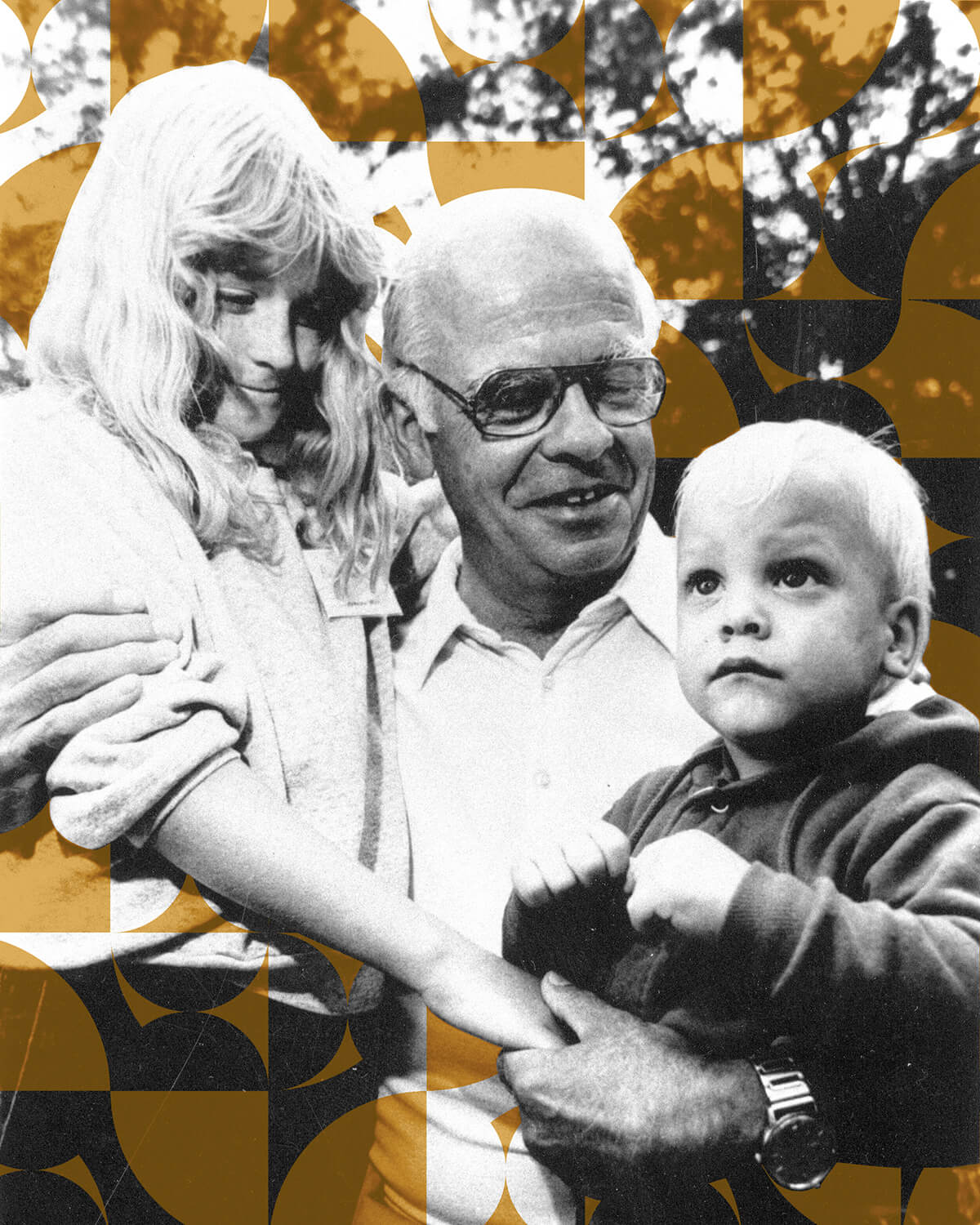

John Bowman / University of Manitoba College of Medicine Archives

Dr. John Bowman [MD/49] would call them “my babies.” They were infants with life-threatening Rh disease, which means they had a protein on the surface of their red blood cells that didn’t match their mother’s, triggering the mom’s immune system to attack while invitro. Bowman, building on the pioneering work of Dr. Bruce Chown [MD/1922], who established the Winnipeg Rh Laboratory in the 1940s, was determined to find a treatment and after a decade of tireless work developed a lifesaving vaccine in 1973.

Naomi Hinz, now in her 40s, was among the Rh babies Bowman treated. She was a particularly tough case and required several blood transfusions (Bowman even provided his own blood.) He promised the nurses and doctors a champagne party if she pulled through, and a few days before her release he brought 25 bottles into the hospital.

“It was a gift he gave us from his life’s work. You can never forget that,” said Hinz.

Following Bowman’s death in 2005, many continue to build on his passion to improve child health, including the Winnipeg Rh Institute Foundation, which endowed $1 million to UM in 2019 to help create the Dr. John M. Bowman Chair in Pediatrics and Child Health.

During World War I, UM graduating students belonging to a field ambulance unit in France lifted their spirits by staging their own Convocation. At a rest station for sick troops, following a strenuous winter that culminated in the capture of Vimy Ridge, they recreated festivities.

In addition to gowns, the grads made academic hoods—out of sand bags. Pseudo university dignitaries then wore strips of gauze and bandages they’d stained a variety of colours. Despite the light-hearted tone, the ceremony carried real significance for the enlisted grads.

Fast forward to today’s grads…UM recently celebrated The Max Rady College of Medicine’s latest white coat ceremony attendees—the Class of 2027—which had a record 125 med students. With the College’s trailblazing admissions policy to better reflect Manitoba’s diverse population, the graduating class includes 66 women, 57 men and two students who identify as no-binary—10 of whom are Indigenous and 59 who have a rural connection.

Manitoba Medical College / University of Manitoba Archives & Special Collections

In the beginning, the Manitoba Medical College relied on volunteer instructors and had no permanent space of its own. A small cottage on Isabel St. near Notre Dame Ave. would serve as its first anatomy lab. In 1919, the College—by then with its own building on Bannatyne Ave. and Emily St.—became the Faculty of Health Sciences. Decades later, the faculty would bring together medicine with dentistry, nursing, pharmacy and rehab sciences.

Two years after the amalgamation, the College changed its name to the Max Rady College of Medicine when Ernest Rady [BComm/58, LLB/62, LLD/15] and his wife Evelyn [BA/60, BSW/61, MSW/67], through the Rady Family Foundation, announced a $30-million gift in honour of his parents Rose and Dr. Max Rady [MD/1921], a Winnipeg physician. At the time, it was the largest personal donation not only in UM history but in Manitoba.

Today the Max Rady College of Medicine is still the province’s only medical school and is known for its leadership in interprofessional collaboration and a robust research enterprise in the clinical and basic sciences.

The questions are interesting