Artifacts

Fall 2020

Biological anthropologist Stacie Burke is driven by one goal: to understand what it is to be human.

Traveling back in time to explore how the spread of illness shapes us, she studies epidemics as early as the 1800s, looking at diseases likes yellow fever, cholera and tuberculosis. They can affect our biology, shift the demographics of entire populations and trigger profound cultural and social change.

“You try to understand the complex dimensions of a population as much as you can—social life, political life, economics—and you look at how disease operates within that context.”

We asked the UM professor, who was self-isolating in Ontario, to take us on a tour of her COVID-era home office. Here’s what we found:

Sputum collectors from early to mid-20th century, when bylaws curbed spitting in public to combat tuberculosis. Those with active disease kept small ones like these in pockets or purses to capture coughed-up phlegm and bacteria. “I found these on eBay years ago. They’re interesting artifacts and fun to bring to class.”

Old photo albums of strangers, some bought at auctions. “I like to flip through, imagining the stories. They make me curious about what their lives were like, how they were living, what their houses looked like, what they were doing recreationally—it engages the anthropologist in me.”

One album in particular, full of portraits of people wearing pajamas, laying in beds and posing on balconies, inspired her research of sanatoriums in Ontario, where TB patients sought specialized treatment.

Stacks of newspapers delivered since the pandemic emerged. She was intrigued that even the entertainment and homes sections were COVID-infused. The horoscopes, at first, came with the disclaimer they were written weeks prior and going forward would be more pandemic appropriate. “All of these dimensions fascinated me, but it was hard to keep on top of it, so my pile of newspapers has accumulated, ready for future scrapbooking.”

Old Eaton’s catalogues from the 20th century—the same era in which she’s researching changes in the practice of biomedicine. “I use them to visualize the material culture of past eras—the kinds of toasters people were using, that kind of thing. But the catalogue is itself an artifact of its time and, as one who teaches in the area of human variation, it displays a notable lack of diversity.”

A photo of a 1907 self-portrait by Paula Modersohn-Becker that Burke snapped at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The German artist is believed to be the first expectant mother to paint herself. She died later that year of complications from childbirth. “I realized how much understanding the artist within the context of their life could impact how a painting is viewed.”

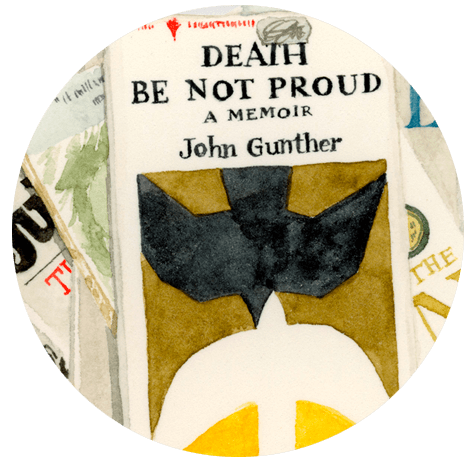

Published illness memoirs, some written by people who had experienced cancer, or survived a stroke or were struggling with addiction. “Searching for these at bookstores and thrift shops, I was surprised how quickly my collection grew. There’s a pervasive desire to reflect upon personal health, with authors finding meaning not only in the writing but also in the sharing.”

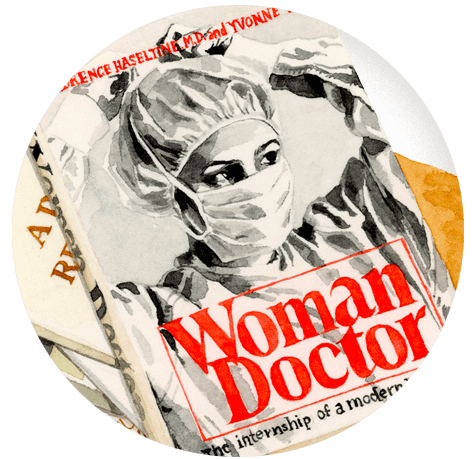

Published narratives of medical professionals in biomedicine, including 19th-century rural physicians who would travel by horseback. “Alongside the patient experience, I’m also interested in how doctors and nurses reflect on their profession and practice. It helps me to better understand the changing culture of biomedicine.”

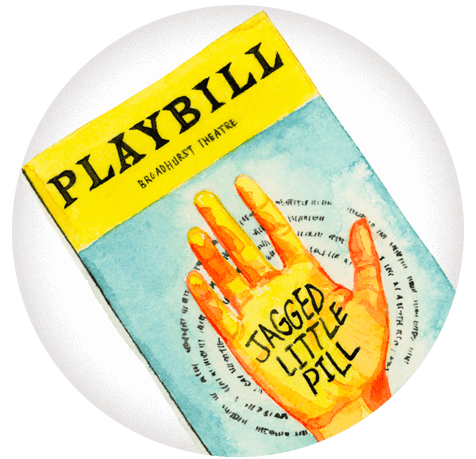

A memento from a February visit to New York, just before it was seized by COVID-19. Burke was there for a workshop, part of Columbia University’s certification of professional achievement in narrative medicine. During a recent hiatus from teaching following her father’s death, she became a student. “I was thankful for the opportunity to take a leave in my work this past year—a therapeutic pause which I have lived as my creative year.”

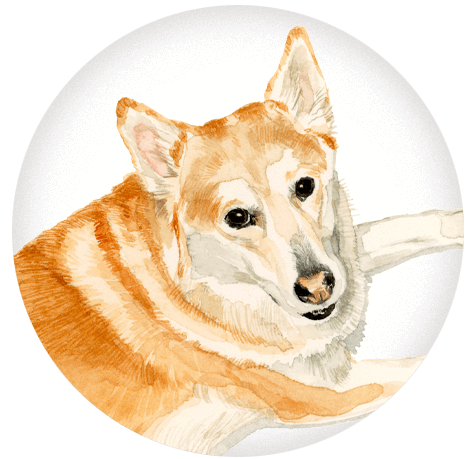

Her dog, Oakley, who spends most of her morning sleeping in Burke’s office, relocating elsewhere after lunch. “She’s good company and offers me an excuse to pause and pet her while I gather my thoughts and then return to writing again.”