It smelled damp. Earthy. But it wasn’t yet as humid as it would be later in the day.

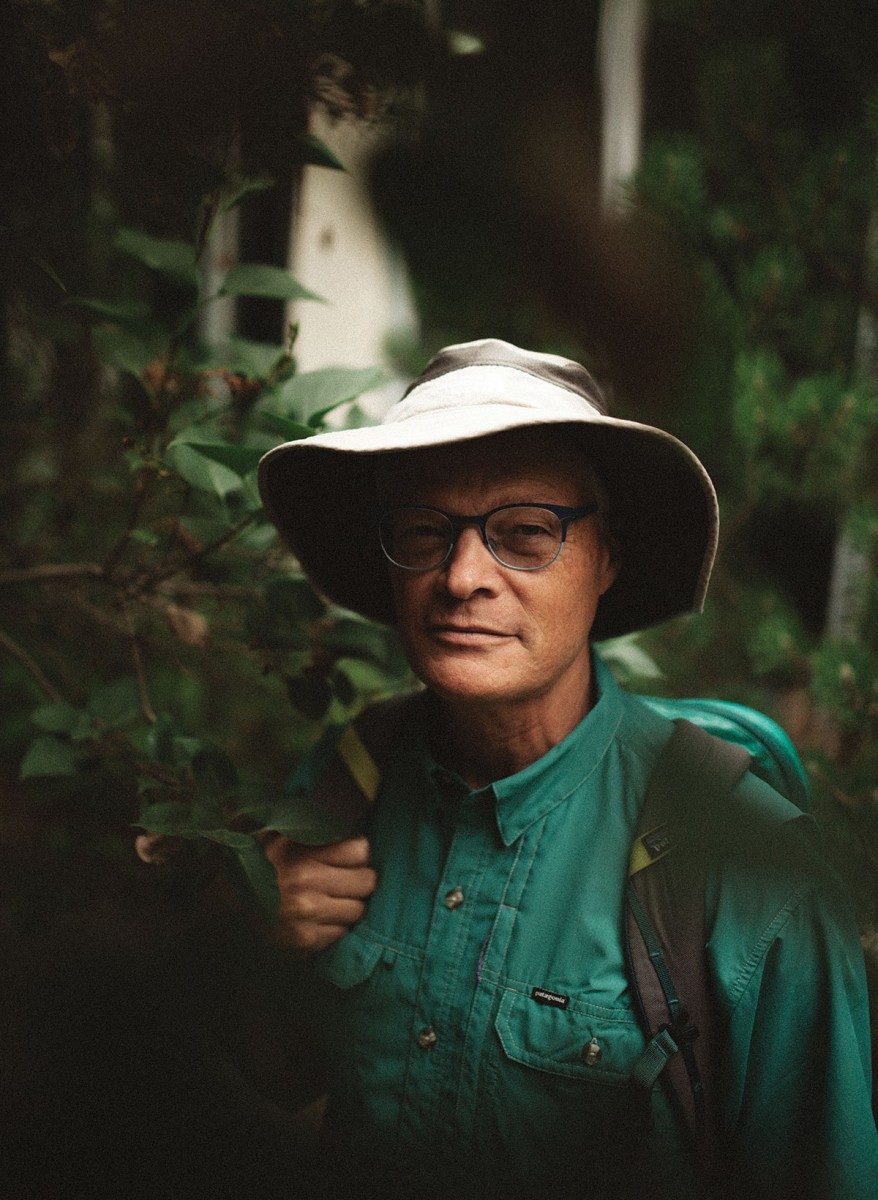

Scanning up and down, botanist Bruce Ford trekked past banana trees and other lush plants in the wilds of Vietnam. He and his colleagues had slept overnight on the floor of the ranger’s station and were ready for a long hike. In his backpack was his lunch of tofu and rice, and local bread so fluffy you had to cut it with scissors or risk squashing it with a knife.

The U of M biological sciences professor was on a journey that picked up where little-known French-Canadian botanist Marcel Raymond had left off decades earlier. For Ford, who grew up exploring the wooded ravine behind his childhood house outside Toronto, who went on country-wide camping trips in his family’s ’68 Buick LeSabre, who would choose birdwatching over golf any day, it meant getting into the headspace of an obscure scientist from the 1950s he’d never met. Ford imagined that, like him, Raymond too felt the pull to identify his surroundings, always wanting to answer: What is that?

Their paths crossed at sedges, one of the world’s most diverse plants found in wetlands, tundra and forests around the world, including in Manitoba. Ford believed the secrets of its evolution lay in poorly sampled South East Asia but all he had to go on was Raymond’s mint-coloured book—as thin as a kid’s scribbler—and a grainy black-and-white photograph, labelled Fig. 17, of his unusual discovery: Carex kucyniakii, a peculiar species with distinctively stalked, wide leaves.

Part of the sedge family, Carex is the largest genus of flowering plant on the planet. Raymond cited specimens as far back as the 19th century— many that hadn’t been seen in 100 years.

“It was tantalizing,” Ford says.

“You have to be a sedge geek to really get into it.”

But the location was vague and the tale had another wrinkle: There was only a single specimen in existence and Raymond had received it from colleague Paul Alfred Pételot, a botanist who gathered it in 1944. Ford and the team analyzed old maps and satellite images, reviewed Raymond’s many publications, and even recreated Pételot’s daily routine: He likely didn’t venture too far from his base in Sapa, a town south of the Chinese border. “Botanists are lazy,” says Ford. “It’s the path of least resistance.”

When the team tracked down Raymond’s curious species, there were high-fives all around. In one second, it was a bond to a past.

“You clamber up the side of the mountain and all of a sudden come across this plant that we’ve only ever seen in a black-and-white picture and to see that, oh my goodness, it’s still there—you have to be a sedge geek to really get into it.”

And now Ford and the team were about to make their own discovery. Walking alongside a series of streams not too far away, under a sun that flickered each time giant blue butterflies crossed its beams, they saw them. Sedges like no other. Their leaves were as wide as 12 cm and their flower structures were not green like most Carex, but red. And they were hairy.

“We knew, this is different. This is rare. This is odd. Even in the field, we were sure, you know what, I think these things are actually a new species to science.”

Back home, DNA sequence data and careful study under the microscope revealed even more surprises. Their analyses confirmed not one but two new species: Carex geographica (named after the National Geographic Society, who funded the expedition) and Carex thinii (named after the father of Ford’s Vietnamese colleague). The discovery was published last year in the journal Systematic Botany.

The findings are crucial for conservation, Ford insists. Especially in a country where poverty drives massive clear-cutting to make room for corn crops, caged song birds as pets are “as common as lampshades in people’s homes” and endangered orchids are poached even in protected areas. “You can’t conserve it if you don’t know it exists. Species are being lost before they can be described,” he says.

What Ford found in Vietnam was a heightened sense of responsibility. He hopes to return next year to continue his quest. The specimens he brought back are among the 80,000 that reside in the Herbarium— a room in the Buller Building that serves as a resource for researchers. Each specimen tells a story, and the accompanying label, Ford is quick to point out, includes the name, habitat and even the GPS coordinates of precisely where it was plucked from the ground.

Finding Empowerment

Riding in her dad’s old truck, Sonya Ballantyne [BA(Hons)/08] balanced a container of popcorn chicken on her lap, along with her favourite comic book. The truck was white. The ‘90s windbreaker she wore was multicoloured and reminded her of a parachute.

She was only six at the time and headed home to Misipawistik Cree Nation after a grocery run to The Pas, Man., where food was cheaper. Engrossed by the fantasy of DC Comics, she flipped to a page that revealed a giant piece of kryptonite—just as the bumpy road caught up with her. She suddenly felt nauseated and got sick. In that moment, Ballantyne was certain: She. Was. Superman.

“Or, at least, a Superman-esque person,” jokes the emerging filmmaker, now 32. “It gave me a belief in my own value I guess.”

“Who would Superman be if he had my life?”

At the time she thought, that’s why her grandmother, Virginia, was always telling her to “be more normal.” She was from the planet Krypton.

As a kid, Ballantyne had read every book in the library of her one-hallway elementary school in Grand Rapids, Man., and was the only one among her friends who would skip class so she could read even more. The only one who got wrapped up in the big, bold existence of superheroes— Superman was her favourite. She admits, a hyper-idolized white guy was an unlikely hero for a Cree girl who grew up in a community where Manitoba Hydro had come in and brought with it what always felt like a tense, racial divide.

It never made sense to Ballantyne why she couldn’t roller-skate on the “white side of town” where they had perfectly smooth pavement, instead of the dirt roads of the reserve. Her dad would get mad when she snuck away to the dangerous highway instead.

She remembers when he was bragging about how she taught herself to read at age three, and in response, a parent of a classmate felt it was okay to pull her aside and tell her she wasn’t going to amount to anything. “Because I was an Indian and I was a girl,” she says.

Yet her father taught her to face racism not with anger but with fortitude. Ballantyne would become the first in her family to graduate from high school (her dad’s gift for her was a Harry Potter book) and then the first to graduate from university. Her sister was the second.

She soon discovered the make-believe of movies was what really “lit her up.” And as she became part of a growing Indigenous film scene, Ballantyne pondered, “Who would Superman be if he had my life?” and then created tough, female Indigenous superheroes like Thunderbird, whose secret power is to create storms, in her movie Crash Site—which has since been screened all over the world, from Australia to France.

When she showed the film to kids at a Winnipeg school, they were so quiet Ballantyne worried they hated it. But when the lights came on they rushed her, wanting to know if she would make it longer, and could they be in her next film. She later heard one of the girls had asked if she could be Thunderbird for Halloween. “I’m like, that’s what I want!” says Ballantyne, who is now working on a documentary about how, this past summer, she became the first Cree woman to be a panelist at San Diego’s Comic-Con.

Her greater goal is to change how Indigenous women are depicted on screen—she sees progress for male actors in roles like Davis on Corner Gas and Chief in Wonder Woman.

“But there are no roles like that for women yet. And that’s what I’m trying to make,” she says. “We’re eliminating the stoic Native stereotype for men but we haven’t eliminated the tiger lily stereotype for women, where they’re just, like, hostages and quiet girls who aren’t talking. I want to make girls who are angry, girls who are sacred, and girls who are tough, like all the girls I grew up with.”

Finding Courage

Ellen Judd was right there but could only see them from afar. Each of the five defendants was facing the judge, their backs to the viewing gallery of journalists, survivors and family members of those killed. Of the five rows, accused 9/11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed sat in the first.

The men wore their traditional clothing, provided by the defence counsel seated next to them. They each had with them a laptop and a prayer rug for this second round of pre-trial hearings at Guantanamo Bay.

As Judd peered through three panes of a glass wall, and saw them for the first time, she felt herself wanting to be closer. And yet this University of Manitoba anthropologist wasn’t sure how it would feel to make eye contact with the men accused of plotting the attack that crumbled an office tower as her partner, Christine Egan [PhD/99], stood in the lobby waiting for her little brother.

Egan, a nurse, was in New York on Sept. 11, 2001, to care for her nephew so her brother, Michael, an insurance company executive, and his wife could fly to Bermuda for their 20th wedding anniversary. When the hijacked plane hit the north tower, he sent Egan downstairs while he helped his coworkers in the south tower escape; he was fire marshal for his floor, 105.

“She wouldn’t have left without Mike,” Judd says.

After the south tower was hit, Michael was on the phone with his wife, explaining to her that he was trapped. She quickly phoned Judd, who then watched on TV in Winnipeg as the building disappeared into ash.

Judd was one of five 9/11 family members chosen to witness the judicial process in August last year at the heavily monitored island war court, on the U.S. Navy base in Cuba. “I went there for a deeper understanding of what is going on in response to the killing of Chris, and her brother, and everyone else,” Judd says.

She was thousands of miles away from her character home in Winnipeg—the one Egan knew she wanted the moment the realtor brought her there three decades ago (Judd thought they were checking out the market; Egan had other ideas.) A world away from the blue flowers Egan thoughtfully stencilled on the risers of the stairs, that Judd has been careful not to paint over.

She now found herself with an intimate yet arms-length view into a historic and drawn-out process of a controversial military commission system to convict during the War on Terror—one shrouded in torture complaints in the 11 years since the first co-conspirator was arraigned. “It’s a very complicated legal and moral tangle—you see wrong on all sides of it,” she says.

It all felt so disjointed as the gallery listened on a 40-second time delay to guard classified information. She heard defence lawyers accuse the judge and prosecutors of secretly allowing the destruction of a covert American interrogation site—believed to be where Mohammed was tortured—as well as the evidence it contained. She also heard a defendant speak of debilitating sleep deprivation from constant noise, and another of his difficulty sitting in the courtroom due to internal injuries caused during his CIA “enhanced interrogation.”

So much effort had been given to retribution; Judd wanted to shift the focus from penalty to prevention. This professor who teaches about the anthropology of war, and of human rights, wanted to say something that would help reduce conflict in the world and prevent further civilian deaths—each person lost to terrorism with a story all their own.

For British-born Egan, hers included a love of Nunavut. She earned her PhD in community health sciences from the U of M at 53, and was drawn to how welcoming the North felt to outsiders. It was so easy for her to fall for these small communities. “But she liked almost everywhere she found herself,” Judd says.

Egan was the extrovert, who would goof around with her nephews wearing reindeer antlers.

Judd, the introvert, would tell reporters in Guantanamo: “The taking of these lives would not give Chris another moment of life and would not give me any relief. May this be a time for turning grief into compassion.”

“It’s a very complicated legal and moral tangle—you see wrong on all sides of it.”

This despite not seeing any remorse among the accused. At first she wasn’t sure how the other families would feel when she spoke against the death penalty, which some sombrely endorsed, even the survivor she met who was “full of such gentleness”—the one she took a photo of with an iguana on the lawn outside during break. Throughout the week, everyone was quietly reassuring of each other.

Soft-spoken but unabashed in her willingness to be witness, Judd feels a duty to help create change given her unique capacity in academia— otherwise, she says, she would never put herself through this. She hopes to return to Guantanamo before long, to see more of the hearings. The trial could begin as early as next year but is plagued by delays. “Anthropology is the study of humanity,” Judd says, “and if we can’t bring our own humanity to it, and connect with other people, then something is missing.”

She suspects when anthropologists of the future look back at our modern era, they’ll be analyzing this permanent state of war, and its escalation.

In an unlikely probability, terrorism also took the life of a friend who spoke at Egan’s funeral; he was killed in the 2008 Mumbai attacks. In Judd’s academic work, she talks about these threshold moments of war and upheaval, and how they lead to new possibilities. Historically, she says, change is created in the aftermath.

“If the world shifts beneath our feet, what do we do about it?” she says. “What is essential is what is done—what people do—in the long days after.”

Finding Resilience

Sheena Grobb [BSc/05, BEd/07] knew something was wrong the second she woke up. The left side of her body was numb, but she felt defiant. Grobb was 23, a second-year U of M education student, and wanted to go about her morning routine. Reality set in when she couldn’t wash the shampoo out of her hair.

The tears came slowly as Grobb recognized what she was facing: her second major relapse from multiple sclerosis since her diagnosis at 16 (it was Christmas Eve when she learned her symptoms weren’t from a pinched nerve after an intense track meet, as she had hoped.)

With no control over part of her body, how would she do her teaching practicum now? And what about her music? Grobb was a budding singer-songwriter, who didn’t yet know one of her future albums would be mastered at Abbey Road Studios, the prestigious London-based recording house of the Beatles. (When her Winnipeg producer reached out on a whim, they immediately said yes.)

“I see it now as something that allowed me to course-correct how I was living my life.”

Standing in her kitchen, she questioned whether she could play the piano or her guitar again if she couldn’t even hold a tea cup. With a voice that’s been compared to that of Sarah McLachlan and Norah Jones, Grobb knew at any time MS could also affect her speech. At one point, her vision diminished so much it felt as though she was looking through a screened door with half the holes filled in.

The paralysis-like symptoms endured a month and proved to be a major turning point for Grobb.

“It was definitely one of those moments I will never forget,” she says. “But also, I see it now as something that allowed me to course-correct how I was living my life.”

She grew up on a farm in Treherne, Man., in a loving homestead that also included her grandmother, who would repurpose old clothing into sweeping patchwork quilts that were the perfect canopy for making forts.

When her grandma lost her battle with breast cancer, Grobb wrote her first song. She was only 10 but the lyrics still feel profound and, she says, like a message to her older self: She smiles at me so beautifully but you can’t hear her scream.

“I think I was imagining what her experience was,” Grobb says.

She set her own journey to lyrics years later in the song Get Out Alive, written immediately following her MS relapse, which she says pushed her to live for herself, not to please anyone else, and to put her health first.

Grobb later got a call out of the blue from a So You Think You Can Dance choreographer asking if the TV show’s top dancers could use the song for a video. “It was surreal, like Oprah calling to borrow a sweater,” she says.

With three albums to date, Grobb is set for another release this fall—this time, a collaboration with Nashville producer David Kalmusky, who’s worked with John Oates of famed Hall & Oates and with Journey. Teaching-wise, she’s shifted her focus from high school chemistry teacher to health coach for others living with chronic disease. It was her experience as a student volunteer in a U of M peer advisory program that made her realize she wanted to help others.

The lessons learned in her journey have informed a new philosophy that has her and husband Dan Legrand adopting a more minimalist lifestyle. The couple is building a tiny house, only eight feet wide.

“We’re both musicians and enjoy living life in the wild, being out in nature, having fewer things. We’ve been giving away most of our possessions over the last year and have come to a place of true peace,” she says. “Everything feels light. I still want to build a big future for myself but in a different way, through giving back, contributing something real and honest, not through acquiring items I don’t really need, or keeping up with the next big thing.”

She’s even gifted the huge digital piano she’s dragged with her from place to place over the years, in search of one that’s a better fit.

Finding Gratitude

Construction Park. That’s where Angela Taylor [BA/06, PBDip.Ed/16] was headed but she had no idea where to go.

Her blue-eyed boy, Liam, had been diagnosed with autism as a toddler and now, at six, was in the back of their minivan repeating himself as they drove to a planned visit to the “French fry store.”

Construction Park. I want to go to Construction Park, he said over and over. Taylor couldn’t figure out the detour he was requesting so she retraced their route. Was it a playground that had roadworks nearby? Or a park with a building theme? In fact, it was a play structure they’d never even been to, painted bright yellow like a construction worker’s safety vest.

No one else in the van (not Liam’s siblings or his mom) saw this hidden gem masked entirely by trees—what would have been a sliver of yellow in a quick break in foliage whirling by at 50 kilometres per hour. In that moment, Taylor saw the unique strength of her son so clearly and thought: How brilliant is he?

“He sees things in a much more detailed way,” she says. “How brilliant is he to see the world that way? What a blessing in my life to see the world that way, too.”

A blessing that overrides the hurdles—and there have been lots. So many that five years ago Taylor started Inspire Community Outreach Inc., an organization to help catch children being left behind and frustrated parents trying to navigate an incomplete support system.

Taylor has worked for years as a service provider to kids with complex needs, those she describes as neuro-diverse—even before her own child was diagnosed—and has uncovered gaps everywhere: in the literature, in the response of teachers and government care workers, in the swim class instructor who forgot to catch Liam when he jumped in the water (weeks later, Taylor is still working to regain lost trust).

“As I’m showing compassion, I’m gaining compassion for myself.”

“No matter where you go, you’re not expected. You’re not planned for,” she says.

Educating others is tough when autism can present so differently. “If you know one person with autism, you know one person with autism. Liam’s one of the most beautiful people I’ve gotten to know,” Taylor says. “He likes to be tickled, to race, jump in piles of pillows and be squished. He’s just a really sweet, loving soul.”

He’ll repeat phrases with the same inflection in which he hears them— for some time, that meant mimicking Thomas the Tank Engine. His parents loved that he was talking at all and would call him “British Liam.”

How little he spoke was an early red flag. When he did talk, he would repeat the same word a hundred or so times, and then never say it again. When his tantrums lasted eight hours, the doctor told Taylor her son would outgrow it, and to put him in front of the TV if that was the only thing that could settle him. A delay in diagnosis meant a delay in care.

“The world is not made for this type of disability—yet,” says Taylor. “I’m working on it.”

The Inspire agency takes its cues from the client, bridging resources when families face years of wait lists and bringing mindfulness and a sense of peace to kids through art, nature and hatha yoga. Taylor says the work, which extends to help not only those with cognitive differences but those coping with mental health issues, is good for her own well-being. “As I’m showing compassion, I’m gaining compassion for myself,” Taylor explains.

What she’s learned as a mother to Liam builds on what she already knows as the daughter of Sharon.

Taylor was the first-born to a 21-year-old mother trying to do her best while coping with a mental illness that meant, for some stretches, she slept for days, and others not at all. Taylor remembers being home alone as young as age three, hiding between the sofa and the living-room wall, plugging coloured pegs into her Light Brite.

She also remembers the first time her mother tried to take her own life with pills. Taylor was four.

When designer Kate Spade’s suicide note to her daughter made headlines earlier this year, Taylor circled back to the memories of a loud knock on her front door and two RCMP officers on the step. She dropped to the ground when she learned her mom, who had been in and out of hospital for years, was gone at 41, leaving behind several handwritten pages scribbled in her last moments. That day, Taylor became a parent to her baby sister and now counts the 18-year-old among her four children.

Bipolar disorder was the label that followed her mom. Taylor grew up attached to a few, too: dyslexia, anxiety, ADHD, PTSD. “I’ve had a lot of trauma growing up and that changed my neurology forever and I don’t see it as bad anymore,” she says, noting how her life experience helps her “get” the kids and teens she works with.

She knows her youngest son will grow up with “labels he’s been assigned”—but also with his own gifts, revealing themselves every day. “Exceptional is so much nicer than disability,” says Taylor. “Whatever your struggle, whatever your history, it’s okay.”

Now a disability studies master’s student at the U of M, she is looking at the missing pieces in the landscape of care for those with mental health issues or cognitive differences. There are no tidy solutions.

“Being a human is complex,” Taylor says. “It’s messy. It’s beautiful.”