At Discovery Children’s Centre: Outdoors no matter the weather.

Outdoor play and the everyday

Why educators and architects are calling classrooms ‘cages’ and swapping out structured curriculum for campfires

With winter’s cold setting in, many Manitobans might feel the urge to fire up Netflix and hibernate. But what if we took a cue from the growing number of kids — from toddler to school-age — who are learning early in life to embrace being outside no matter the weather?

Discovery Children’s Centre in Winnipeg’s St. James neighborhood used to ban their kids from playing in the puddles; now they gear them up in full-body rain suits and let them loose. Here, kids navigate boulders, climb trees, and dig in sand at least two-and-a-half-feet deep that a couple of times a year gets turned into a massive mud puddle.

The kids are encouraged to get dirty and children as young as two are invited to venture in waist-deep to celebrate International Mud Day. “Cleanliness is a bit lower on our priority list than the great exposure and learning when they get to do things like that,” explains Ron Blatz, the centre’s executive director and a U of M extended education alumnus.

One of the first in the city to adopt this more natural approach to play, Blatz worked bare-bones open grass and chain link fence into a “nature playscape” with trees, hills, stumps, driftwood and garden boxes growing vegetables and prairie crops like flax and canola. The pre-school kids at Discovery spend about 20 per cent of their time outside — roughly four times the Canadian average.

The long-time early childhood educator says it was a conference eight years ago that transformed his approach. Guest speaker Jim Greenman (author of Caring Spaces, Learning Spaces: Children’s Environments that Work) asked everyone to close their eyes and envision their favorite place as a kid. Then he went around the room, asking each participant to reveal their cherished locations. At the edge of the lake, in the woods, by the creek, in the tree fort — not one was indoors.

“He said, ‘OK, how many of you are going out of your way to make those kinds of places available to the children your work with? And I was just stunned by the fact that not one person raised their hand,” recalls Blatz, who grew up a farm boy in tiny Kane, Man., and took great joy in playing in the hay stacks. “Not one of us was making the effort, nor had I even thought of bringing in hay bales to our property. I just didn’t. That impacted me…. I thought ok, that needs to change.”

The movement to bring back outdoor play is booming, he says. “It’s growing faster than you can imagine.” Blatz fears classrooms are too cage-like and insists kids’ behaviour and development thrive when there are no walls to hold them back. A look at the outdoor classroom trend emerging in Canada suggests he’s not alone.

Students enrolled in Forest Schools — a concept born in Europe — can spend the entire day learning in the woods or in a park, their instructors deriving their curriculum from nature. Forest School Canada lists a dozen “forest and nature-based programs” across the country, from Maplewood Forest School in Guelph to the Fresh Air Learning program in Vancouver. The funding for schoolyards announced this month by government officials in Manitoba included the addition of an outdoor classroom at La Barriere Crossings School.

This past year more than a dozen kids from Blatz’s centre — along with three other daycares — took part in a pilot forest school at Fort Whyte Alive. Blatz also wants to develop his own forest in the field adjacent to the centre, complete with marsh, meadows, fruit trees, and features like a cookhouse. He’s been seeking permission (but so far, unsuccessfully) to transform the land — used during the evenings for three months a year for soccer — into a year-round natural wonderland for the 300-plus kids in his and the adjacent daycare, along with other neighborhood kids. It can still be an uphill battle to convince others about how important it is that children develop a love for the outdoors — and a desire to take protect it — early on, Blatz says.

“We know if they don’t learn to love nature they probably won’t be motivated to take care of this planet when they become adults. So we’ve got a task in front of us to get them to fall in love with nature, give them lots of great outdoor experiences,” he says. “We’re not going to lecture them about recycling. They need first-hand experience.”

Blatz: Children need first-hand experience with the outdoors.

A few years ago, a Discovery staff member came up with an idea to spend an entire two weeks outside where children as young as two spend all day outdoors, rain or shine. Their parents drop them off and pick them up at outdoor tents; staff members even drag the cots outside for nap time. Portable diaper and hand-washing stations are set up so the youngest ones — babies under age two — can spend a portion of the day outside too.

The idea caught on and now schools and daycares across the country take part in this Winnipeg-born challenge, from Sault Ste. Marie to Vancouver Island, and including 33 in Manitoba. A Grade 5 teacher in Winnipeg who ditched the classroom for the outdoors told Blatz the more her students were outside, the more they wanted to be outside and the more creative her teaching became.

Over the years a mentality emerged of being overly cautious in childcare, Blatz explains, and it drove kids indoors. But a lot of risk is perceived, he insists. “There is risk in living but we think that kids can learn to be risk managers. And we can learn these lessons early if we let them.”

***

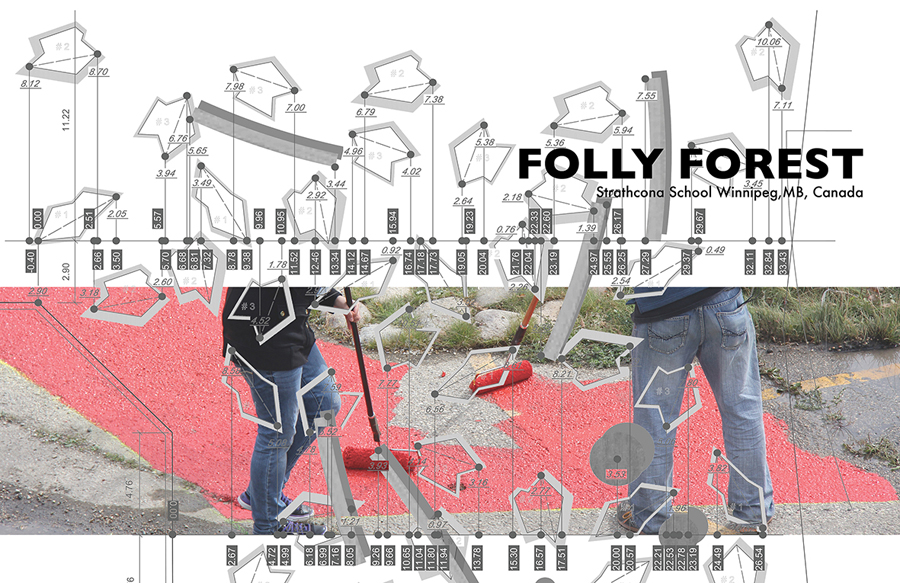

The teacher at Strathcona School in Winnipeg’s North End wanted to know from U of M’s Dietmar Straub, the landscape architect behind their new outdoor space, what exactly were those large slabs of wood for? Were they benches? Tables?

Straub had strategically positioned the wood — pieces he’d salvaged from the city’s demolished stadium — outside the elementary school but was less concise in their purpose. At the time he told her: “I don’t know; you will see.”

Turns out they make good balance beams.

German-born Straub describes himself as someone who believes in children’s creativity. The assistant professor of landscape architecture works and designs at the forefront of the return of unstructured outdoor play.

Instead of building conventional play structures, Straub builds hills.

Perched atop of this lookout point, kids feel like heroes, he says. They see beyond that fence that keeps them in their school or daycare zone.

Instead of installing swing sets, he installs random, intriguing objects to exercise the imagination.

Two massive metal cauldrons some six-feet in diameter sit overturned at Strathcona School, salvaged from a scrap yard outside of Winnipeg. What are they for?

“I think the kids will be able to figure it out,” he says. “It’s what I call creating opportunities.”

Straub suggested to the students they are lookout towers for earthworms. Or a nesting place for dinosaur eggs. A music teacher told him they make interesting sounds when hit with sticks. Straub was adamant that they be left in their original rusty form, calling its patina beautiful. He wants the kids to enjoy the texture.

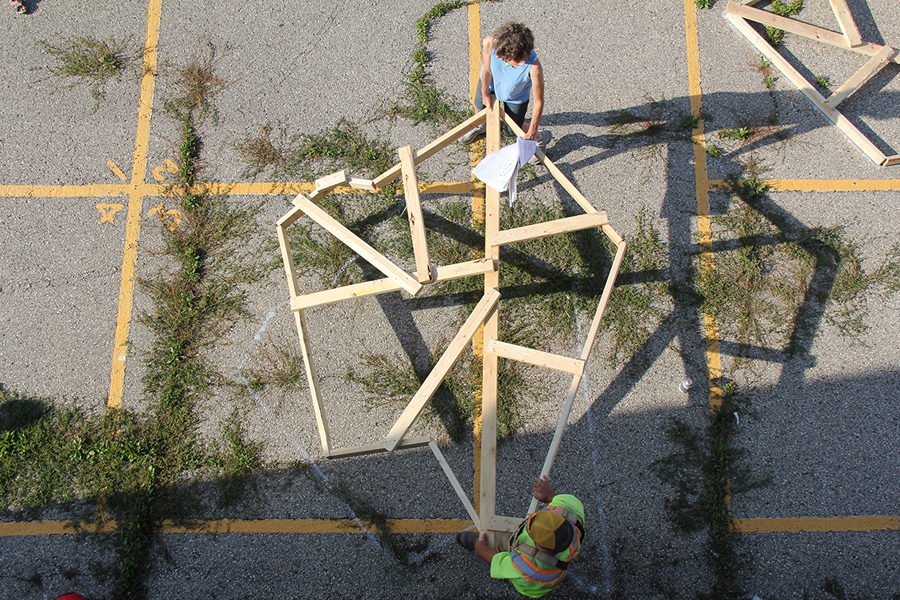

The cauldrons sit opposite the school’s aging asphalt pad, where he busted up star-shaped pieces in order to plant trees. The kids exiting the school now walk through what he calls ‘The Folly Forest.’

Straub does these low-budget projects pro bono with his wife Anna Thurmayr, who is also a landscape architect assistant professor at U of M, as well as his business partner in the firm Straub + Thurmayr Landschaftsarchitekten. This inner-city project recently won the pair one of the most prestigious awards in German architecture — the Deutscher Landschaftsarchitektur Preis 2013 — and in Canada, a National Citation at the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects Awards of Excellence.

They’ve contributed to the design of outdoor spaces across the globe, including one of the largest botanical gardens in the world: the 10-plus-acre Chenshan Botanical Garden in Shanghai, China (project images). But Straub says it’s these small-scale, homegrown projects that he loves most since they give him a chance to add “character” and “atmosphere” to childhood.

Straub grew up in a village of 1,200 in southern Germany and with his brother and sister would explore the family farm with its chickens and geese, and play in the nearby orchards and vineyards. When Straub, Thurmayr and their two young kids moved to Winnipeg six years ago he was shocked to discover daycares operating out of basements.

In Europe, school administrators have long encouraged kids to learn outdoors. Germany is home to hundreds of forest kindergartens (called Waldkindergartens). “Right from the beginning they are allowed to use fire and knives. There, it’s part of the pedagogical process,” he says.

Straub: “If you go to absolute safety, you are very close to very sterile spaces. I always try to open this discussion: How much risk are we willing to take?”

Straub’s parents — a toolmaker and a stay-at-home mom — gave him the freedom as a kid to discover.

“It was so great. There was so much freedom. We were always allowed to take risks,” he says. “And that was super inspiring.”

The father of two says he “creates freedom for children.” Allowing for risk is a key ingredient in his landscape design, which isn’t always an easy sell in an era of helicopter parents. Straub’s view: to keep preschool kids from falling down a hill and hurting themselves, teach them how to climb.

“If you go to absolute safety, you are very close to very sterile spaces,” he says. “I always try to open this discussion: How much risk are we willing to take?”

His architecture students help bring these outdoor play spaces to life and in the process learn about Manitoba’s sometimes overlooked and inexpensive resources. Together they’ve sought farmer’s field stones, trunks from fallen trees on a golf course post thunderstorm and uncontaminated crushed limestone left over from industry. Straub likes to trace the origins of the materials he uses.

Straub: “It’s about a journey.”

“It’s about a journey,” he says.

“If I design somewhere, I need a feeling for the landscape. I need to know where are the materials coming from? What are the stories and sediments of a landscape? So it’s a great opportunity to research that. You can go to the Ice Age and even further to explain why these materials are there.”

He has a habit of using the conventional in unconventional ways: he designed a low-weed, easy-to-maintain vegetable garden — dubbed Instant Garden — for a Winnipeg family out of sand bags typically used to protect homes during prairie flooding. The unusual garden earned several awards, including an honourable mention from the 2011 Design Exchange Awards for landscape architecture. Rows of sandbags covered the yard, within which holes were poked to plant vegetables like zucchinis, tomatoes and pumpkins.

Straub is quick to note that the expanse of sandbags also doubled as a fun place for the kids to run and play.

“Is it a garden? Is it a playground? It’s a little bit of everything.”

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.

very inspiring, loved this story

In education, this concept of outdoor play has been around for a long time, but few have embarked on this journey…this is an invaluable part of growing and learning and supports Indigenous world views not only of children, but how children learn in meaningful ways.

What a fantastic place for children to play and learn. Nature has so much to teach us all and we like this fun environment that was created. Children of all ages can enjoy this terrific space.

PlaSmarttoys.com

@PlaSmart

This is my first time visit at here and i am actually impressed to read everthing at one place.