Carved by Coast Salish artist Luke Marston, the TRC Bentwood Box is a lasting tribute to all Indian Residential School Survivors. The box travelled with the TRC to all of its official events. // Photo by Adam Dolman

Traditional Knowledge Keepers: ‘Now is about restoring’

As Chief Ian Campbell sat with an Elder, he asked, Why are we meant to go through such hardship as a people? The response? “Who are you to question the Creator?”

A descendant of the Squamish and Musqueam First Nations of the Coast Salish People, Campbell is the youngest of the sixteen hereditary Chiefs of the Squamish Nation. He was speaking at the final event of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a two-day Traditional Knowledge Keepers Forum that took place on June 25 and 26 at the University of Manitoba. The TRC brought these traditional knowledge keepers together from across the country for a forum on “reconciliation” that was livecast around the globe.

“When we talk about reconciliation,” Campbell said, “I think about my abuser who took advantage of me as a little boy — and I think of Canada and all of the factors that have brought us together here today.”

He referred to fire — the “fire still needed to be added” for transformation to occur as the same power of “the ember of light, the spark that ignited various realms of existence.”

He continued, “We all have memories of supernatural beings, tricksters and transformation stories … and we have our own stories of our lineage…. Suffering is necessary — you must go through the fire to get to the other side.”

He contrasted the teachings he heard as a boy — of love and respect for all beings — with the hardships wrought by the Residential Schools era and colonialism, removing Indigenous peoples from their own culture. “How do I find value — how do I move beyond blame, shame and judgement?” To make the shift, he said, it “starts within myself.”

Campbell: “What time is it? It’s our time.”

However, he added, “we now have the language for this [the legacy of Residential Schools and colonialism] to be discussed” publicly on this level, and noted that Vancouver has just declared itself a city of reconciliation.

“I believe in adaptation rather than assimilation,” said Campbell. “Tradition is today … it’s constant adaptation.”

Later he spoke again, this time about his nation’s tradition of using red clay on the young men going into ceremony. “We do it to show the ancestors, spirits, the Creator, that we are ready to step into our responsibilities.”

He told those gathered, “I appreciate the healing that has taken place, in this safe space that has been created for us here.

“What time is it? It’s our time.”

***

Mary Deleary shared words from an Anishinaabe teacher, who had taught her about the four directions. The first responsibility is to ourselves, said the Algonquian Anishinaabe mother, grandmother and Three Fires Midewiwin, who originates from Kitigan Zibi (Garden River), Quebec. “The second is to our land.”

His teaching of “the two roads,” she told those gathered, means that “where we stand [influences] how we understand the four directions. The [European] people who came across the water to our land, they must have four directions, too. Our relatives across the water, they also have teachings to share.”

Fundamental to four directions teachings, she said, are “honesty, sharing, strength and kindness” — the four sacred medicines which each represent one of the four directions.

Deleary: “Now is about restoring.”

“I have a hard time understanding “reconciliation,” she continued, “but I understand the four directions — and that is what provides healing.

“The right hand, we shake hands with that hand … it’s the hand of sharing and responsibilities. With the left hand, we hold our ceremonies, defining who we are. We don’t let this one go.”

The past 100 years have been about forcibly removing those ceremonies, she pointed out.

“Now is about restoring. What was forcibly taken and what will they help to restore?”

***

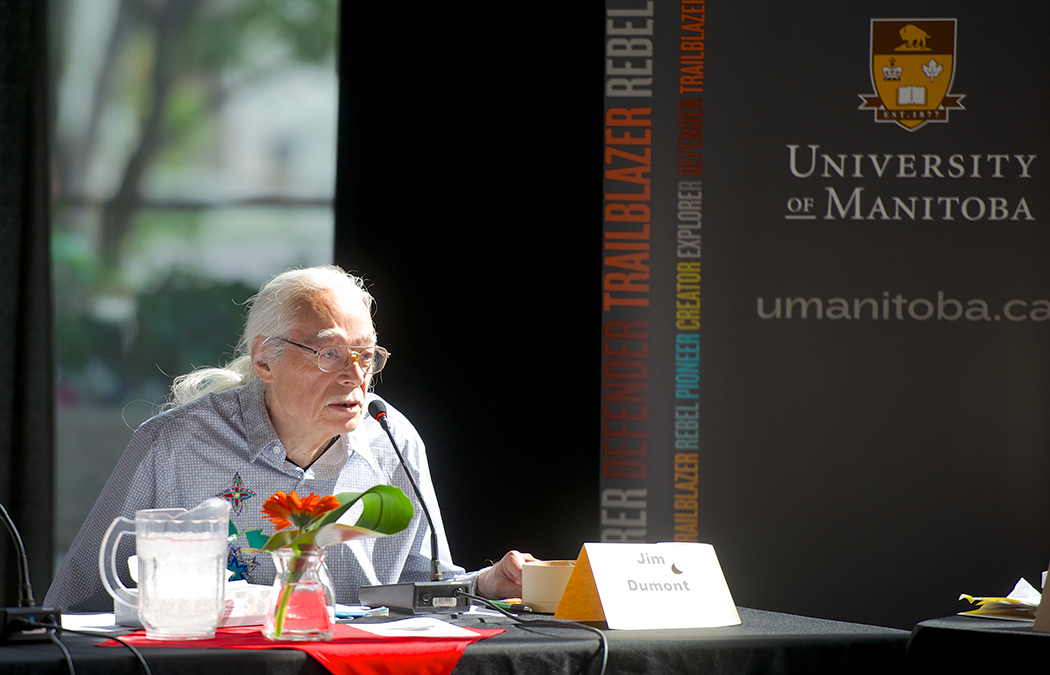

Jim Dumont spoke extensively about the words “truth” and “reconciliation.”

The soft-spoken Chief of the Eastern Doorway of the Three Fires Midewiwin Lodge is Ojibway-Anishinabe of the Marten Clan, originally from the Shawanaga First Nation on Eastern Georgian Bay. He is also a founder of the Midewiwin Society (or Grand Medicine Society) and one of the founders of the Native studies department at the University of Sudbury of Laurentian University, where he was a professor for 25 years. He has also served as a spiritual advisor and laughingly called himself Justice Murray’s “spiritual bodyguard.”

The word for “truth” in Ojibway, he said, is “the sound of your voice as you speak from the heart. It doesn’t literally mean facts. In Ojibway thinking, to speak truth is to speak from our hearts.”

Speaking about forgiveness, Dumont referred to “healing practices” as opposed to “pain inflicted on people who are already in pain by insisting they have to forgive.”

In the way the word is primarily used in Ojibway, it means “to forget,” or “the act of forgetting,” he said.

Smiling, Dumont mentioned a line from a song by “Elder” Bob Dylan: “Even Jesus could not forgive the things that you do.”

His point was a serious one. “Maybe there is some truth there. If someone violates a child and it cripples almost their entire life … is [forgiveness] possible? Is that required? I can’t help thinking there’s something wrong there.”

Dumont: “If someone violates a child and it cripples almost their entire life … is [forgiveness] possible? Is that required? I can’t help thinking there’s something wrong there.”

The word used for “forgive me,” he went on, is an old word and is the original word for forgiveness. He said it is the same word used in offering tobacco, and it means you “release” the tobacco.

“You release something. It means, I release it from my mind,” he explained. He said it was also used in burial ceremonies, as a release of the spirit and from the hold that spirit has.

“So for someone who has been violated or abused, [it means] ‘I release this from myself, it no longer has a hold on me.'”

This “lifts” it from the other person, Dumont clarified; “It frees the perpetrator, but it doesn’t absolve them. They still have to get to a place of peace in themselves but you don’t have that responsibility anymore, for them.

“That place of healing we need to get to in our own lives has a lot to do with how we get to or understand reconciliation,” he said.

Dumont: “That place of healing we need to get to in our own lives has a lot to do with how we get to or understand reconciliation.”

Over the years since the commission began (in 2008), Dumont said that “there are things that have disturbed me.”

He described a movie in which Ghandi says to the missionary who has been working with the people (in a good way, says Dumont), “It’s time for you to get out of the way.”

The situation in Canada might be similar, Dumont suggested. “The church has to take responsibility,” he said, including for “their [own] need to reconcile with the Spirit.

“I’m not a Christian, but I have a high regard for this Spirit who came to those people, Jesus. When the Church can reconcile with their Saviour for what they have done, then maybe we can talk about reconciling with them. How can the people of Canada reconcile with this, continuing to hide, not dealing with things?”

Dumont has the ability to dream names, he said, and people often come to him for a name for their child. He told of a dream he’d had — actually a dream within a dream — in which he asked an Elder for the Ojibway word for “reconciler.” The Elder couldn’t think of the word.

“In every community,” said Dumont, “there was a person who was the reconciler. This was his gift, making peace, making things right, restoring the balance in a relationship.” Dumont spent time with two other Elders, neither of whom were able to recall the word.

Dumont said it was something like, “the one who puts things back in good order … something like a mechanic, the one who fixes things.”

***

Elsipogtog First Nations member and hereditary chief on the Mi’Kmaq Grand Council from the Signigtog region Stephen Augustine used the metaphor of the overturned canoe. He spoke about “the Spirit of the breath of life” (given to the wind); if somebody tipped our canoe, ceremony would take place to right things.”

He said that on behalf of his people he would take up the invitation made by Maria Campbell to meet four time per year, with an offer to host one of the meetings.

***

At the end of the two day event, Commissioner Marie Wilson spoke, in part about her journey as commissioner and in part summarizing what she had heard. She spoke “in the spirit of transformation,” she said, suggesting that the commission had been a transformative experience.

Quoting Elder Barney Williams, who gave her the name “Northwinds Song,” she spoke about “things being different because of things we can do differently.”

She reviewed the past two days of the forum, citing Elizabeth Penashue’s concern about the protecting the land, and the points by several women about hands as keepers of tradition but also the reclaiming of hands for making, creating and teaching things. The wisdom shared, she reiterated, spoke to the significance of words and stories, from conversations with grandmothers and respected elders to animals, and pointed to the “clues in the language itself,” including, as many intimated, the importance of song and the concern for the land and the children.

Referring to Maria Campbell’s presentation on the violence towards Aboriginal women, she said, “I honour your outrage. As I heard you, we must find a way to honour those things that will move us to action. Poverty and violence were named, and there was a challenge to the men.

“I also heard commitment and promises,” she continued, “to the health of the people [and the factors of] housing, education and employment.”

The importance of ceremony was emphasized, in relation to the reclamation of self-identity and identity as a people, the reclamation of sacred lands and language, she said.

She echoed the need to “create an ethical space, where everyone is in that space,” and acknowledged the concern that the report not be “straightforward,” but needed to include stories and values. The concern was, she said, with “how do we do that in a report” — reflect the complexity and heart of a people, their identity and relationship to the land, and “guidance as to how do we speak from the heart to a people who seem to think from the head.”

She quoted Barney Williams again, who said, “We are looking for that light. The ancestors are excited by the joy of what we are trying to do.”

Thanking all of the participants for their “wealth of knowledge … and the depth of teaching,” she told the participants that the forum has been restorative to her as well. She offered an image she encountered on her drive to Manitoba to the event: A beautiful, fully-formed double rainbow. She compared the rainbow to an umbilical cord, linking to Mother Earth. Its double nature spoke to her about “what we hold onto and what we can share,” she said.

And as “a symbol that new life is possible.”

Read Part 1 of our special feature on the TRC’s Traditional Knowledge Keepers Forum.

Read Part 2 here.

Read Part 3 here.

Research at the University of Manitoba is partially supported by funding from the Government of Canada Research Support Fund.