Mayoral hopefuls: Transit beyond the BRT/LRT Debate

Finish the busway, expand the busway network, use LRT instead, or scrap the whole idea. These seem to be the options laid out by the mayoral rivals in Winnipeg. Only one candidate denies that rapid transit is a step in the right direction, but the real problems of the mass transit system lie much, much deeper. The dispersed, low-density pattern of suburban land settlement in Winnipeg is difficult to serve with any traditional bus transit systems. Any increase in the quality of bus service will help a route, but if getting to the rapid transit corridor is difficult, the catchment area will be narrow and suburb-to-suburb travel will hardly be affected.

Often the failures of transit system are blamed on consumers and land developers. The situation is more complicated. Internal and external factors have led to this current state.

Internal problem

The governance model works toward mediocrity. The autonomy of management is constrained by the public monopoly ownership structure and policy direction. Transit managers are forced to provide service where demand would not warrant it and to charge fares that do not cover costs.

In most North American cities, subsidies for public transit exceed the fare-box revenues. Winnipeg Transit is better than most; they collect about 50 per cent of their funds from the fare-box. However, with such a deficit, it is hard for management to innovate or even sustain the bus service. Worse, the subsidy drains public funds that might be used to build infrastructure, like the new busway that improves service.

So much public money is spent subsidizing a service that most citizens never want to use, imagine what it could be like if the money was spent on an urban transportation system everyone wanted to use.

Any bus service that is shielded from competition by a regulated monopoly has little or no pressure to change or impetus to improve. It is instructive to compare the adaptation of the railway industry over the past 50 years, with that of the transit buses.

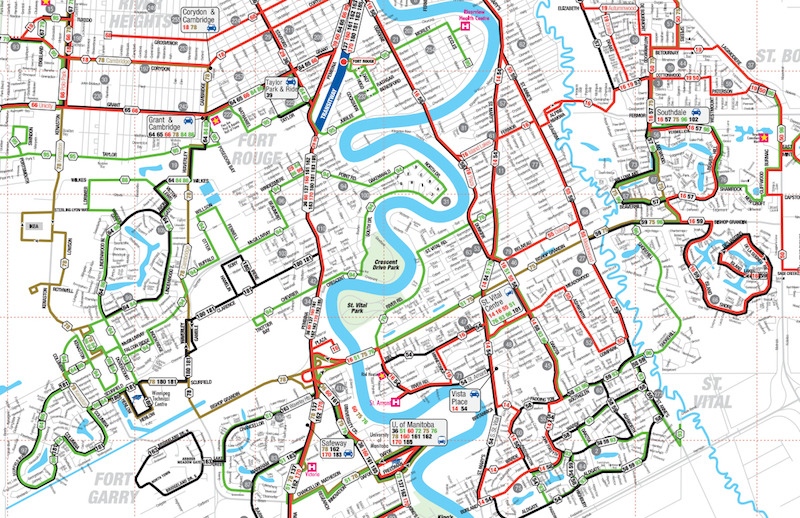

The railways used to operate an extensive feeder network of rail branch-lines, but competition from trucking caused them to discontinue inefficient branches and focus their efforts on the mainline corridor routes. In contrast, the buses still operate a highly centralized route structure of 1950s with extensions into the suburbs. What might have worked well on a grid network is hopeless in new low density settlement patterns of loops and cul-de-sacs. Also, the number of buses per square kilometer did not keep up with the expansion of the suburban areas. Consequently, the service is characterized by infrequent service and long travel times accentuated by circuitous routing and poorly coordinated transfers. Waiting in 20 below for an uncertain transfer at an unheated shelter, or worse in a completely exposed location, is a further incentive to take the car instead.

External Problem

High car ownership is the principal external factor. Automobile influenced urban development has changed work trips, shopping patterns and visiting demands. “Job sprawl” has changed work-travel demand. Fewer people are employed in the Central Business District (CBD), and bus service from suburb to suburb is neither convenient, nor fast. So the commuters that want to ride to work on a transit bus are a narrow slice of the market. Shopping centres and “Big Box” stores similarly attract more customers arriving by car than those coming on foot or by bus. Visiting patterns have changed with population diffusion. Mature children and parents are as likely to live in adjoining suburbs as they are to stay in the family neighbourhood. Similarly, many interest group meetings and cultural events are car-travel dependent.

The failure of bus transit to retain its share of the travel demand has contracted their market to those too old or too young to drive a car, those too poor to own a car, and a narrow population of commuters that still find the route structure acceptable.

Here are some facts that should be accepted:

- The land settlement pattern is set, such that most suburban neighbourhoods are unreceptive to fixed route transit bus routes.

- Private automobiles have desirable qualities and convenience that a system of mass transit cannot match. And most urbanites would think that having at least one car in the family is essential.

- The current transit system of high subsidies and undesirable service qualities cannot do much better than it is already, even with the marginal improvements of BRT/LRT corridors.

If those facts are accepted, then the goal must be to create a mass transit system that is competitive in cost and convenience as the “second car”. However, it is also very clear that any solution must be able to work within the spending constraints of the City of Winnipeg and the Province of Manitoba.

Solution

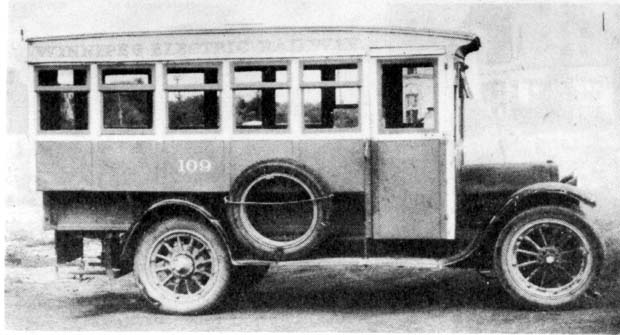

An early transit bus in Winnipeg. Perhaps these mini-buses should return / Image: Archives & Special Collections, U of M

Like the railways, the urban transit systems must divide the two tasks of feeder systems and corridor routes into separate specializations that can do the two jobs most efficiently. The main corridor route would continue to be operated by a publically-owned monopoly and the feeder system would be privatized.

The first step would be to contract the fixed-route system to the main corridors, like St. Mary’s Road, Portage, Main, etc. All the buses serving the neighbourhoods would be shifted to the corridor routes, continuing to employ the same number of buses and drivers, but with greatly improved service times, including better weekend service. The money that was spent on extra fuel and additional revenues from the more attractive service would be spent building climate controlled transfer stations and corridor improvements. The fares on the backbone corridor could continue to be subsidized, but with an eye towards self-sufficiency. To do this, a new operating agency for the Winnipeg Transit would be set up as an independent utility, subject to the review of the Public Utilities Board.

The feeder network would be re-regulated to permit private minibus operators to serve normal and handi-transit demand. The method of operating the minibuses would be similar to the communications technology used by Uber to provide taxi services through the internet. Using GPS and the internet/smartphones, passengers could be picked up at their doors and delivered to the transit terminals. Similarly, they could make the reverse trip from the terminal to their homes on a quick 8 to 10 passenger minibus.

It is true that the total fare to go from the suburbs to the downtown would increase by the cost of the feeder minibuses, and passengers would be expected to pay this. How much the increase would be could also be subject to a Public Utilities Review, but overall, passenger would receive a lot more value for their money.

Part of the resistance to change is the view that we must keep transit fares low to help subsidize low income riders. While this may have been necessary at one time, when cash fares were the rule, the use of electronic fare cards makes this unnecessary. Those receiving welfare, or have disabilities of one form or another, could be given loaded fare cards that would permit a set number of rides per week. This would remove any stigma attached to receiving public assistance and focus the help on those who really need it, rather than wastefully subsidizing the “rich banker’s wife”, too.

Busways or LRT corridors need ridership to be economical. The only means of increasing ridership is to make the total service more appealing. The minibus-public-corridor service offers to provide comfortable transfer points and door-to-door service. A stand-alone agency can undertake the marketing and service refinements to attract more riders. It is a win-win solution that benefits everyone, and an efficient way of creating a service that is at least as good as the “second car” for commuters at a total cost that is far less than they pay now.

Barry E. Prentice

Professor of Supply Chain Management and an associate in the U of M’s Transport Institute in the I.H. Asper School of Business