Jitendra Paliwal (left) adjusts the antennae on the 3D electromagnetic imaging system at the U of M’s grain storage research laboratory while Paul Card (right) watches.

Country Guide: Detecting spoilage before it starts

As the Country Guide (July/August 2017) reports:

An electromagnetic imaging technique originally designed to detect breast cancer tumours is now being adapted for a totally different use — locating spoiled grain in bins.

The research project at the University of Manitoba uses electromagnetic imaging (EMI) to create a 3D profile of a bin, showing pockets of moisture which can overheat and spoil.

The system is the latest development for monitoring storage bins to detect potential spoiled grain, with the goal of helping farmers deal with the perennial problem of post-harvest spoilage losses, estimated to cost more than a billion dollars a year in Canada.

Developers call the 3D EMI system a step up from the current system of temperature-monitoring cables which measure heat levels at different locations inside grain bins.

Paul Card, CEO of 151 Research Inc., says the difference is that EMI is proactive. Sensor cables tell you when there’s a problem in the bin, but EMI tells you before the problem starts.

“Unlike a cable system, we’re detecting the pre-conditions to problems,” says Card, whose firm is partnering with the U of M in the project. “We can give an alert that we’re seeing something that may or may not turn into a problem, and we can give a rough probability of where we think this is going to happen and if something is going to happen or not, unlike a cable system where you’re already in trouble when you receive a detection.”

Card is working with Jitendra Paliwal and Joe LoVetri, U of M professors in the departments of biosystems and electrical and computer engineering.

The idea originated with a 3D microwave imaging system to detect cancer in human breast tissue, developed by LoVetri and his students. It works similarly to a CT scanner but at a much lower frequency.

Paliwal and LoVetri saw an opportunity for grain imaging, but knew it would have to be adapted because a grain bin is obviously very different from a human breast. PhD student Mohammed Asefi adapted the technology to grain imaging.

Generating a 3D image

The team began experimenting by placing small amounts of spoiled grain together with healthy grain in an 80-tonne bin in the U of M’s grain storage research laboratory and checked if the technology could find them. Early results proved encouraging, so they continued testing.

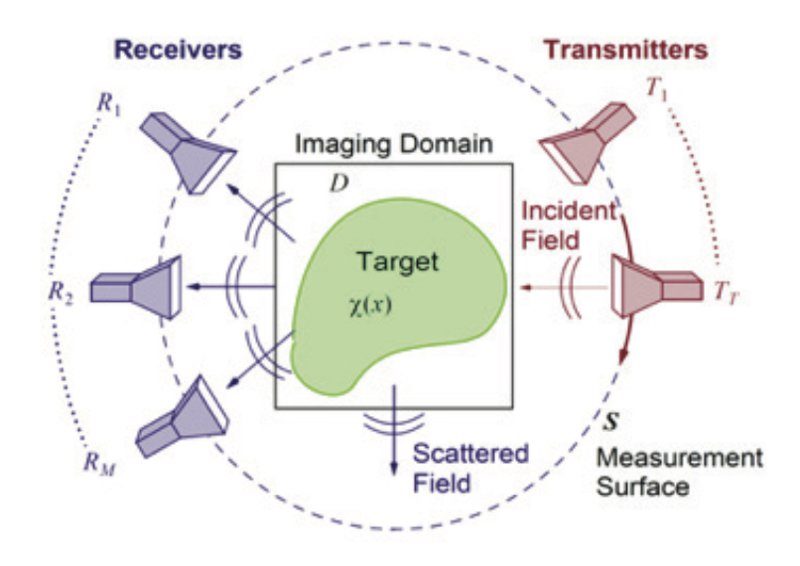

Transmitters and receivers monitor the bin for high-moisture spots. If one is found, the system sends an alert to a computer or cellphone.

Card explains that 24 antennae, acting as receivers and transmitters, are distributed around the inside walls of the bin. A sine wave (tone) is broadcast on one transceiver and received on the others to develop a 3D profile of the bin and its contents. Because grain’s ability to transmit electromagnetic radiation (called its dielectric property) depends on its moisture, it can be used to generate a moisture map like a 3D scan, much like a CT scan to detect tumours.

The information can then be relayed to a computer or cellphone so the producer can read the results without even having to go to the bin.

Card says the main advantage of the EMI system is that it gives a complete picture of what’s happening inside the bin. Sensor cables will indicate a rise in temperature but they won’t say if a hot spot is the size of a golf ball next to the sensor or the size of a beach ball four feet away. EMI pinpoints both the problem and its magnitude, so producers know exactly what they’re dealing with and where.

Another advantage is that the system can indicate exactly how much grain is in the bin. An unexpected drop in volume signals the possibility of grain theft.

Paliwal says there were some problems to overcome. One was the need to redesign the antennae to keep them from breaking during filling and unloading. LoVetri’s lab redesigned the antennae to withstand the forces caused by loading and unloading while still retaining the necessary electrical characteristics.

Paliwal sees a bright future for EMI in monitoring grain bins, especially as bins get larger and hold grain for much longer.

“When bins were smaller, it was easier to sample them,” Paliwal says. “You just opened the door and stuck your head in. But you can’t do that any more. That’s why monitoring grain has become extremely important. It cannot be done manually as we did in the past.”

The use of 3D imaging may not be restricted to farms either. Paliwal suggests the technology could also apply to railcars and ocean vessels — anywhere grain is moved in bulk and where maintaining quality is critical.

Prototype testing this fall

The project is in its final stages of development. Paliwal and Card expect to install up to a dozen prototypes in bins near Winnipeg this fall. A commercialized product is scheduled for release in time for the 2018 growing season. The cost will vary with the size of the bin, but Card and Paliwal expect their system will be competitive with cable monitors.

While acknowledging that the new technology isn’t cheap, Card says the cost has to be weighed against the value of the crop in the bin.

“If you spoil one bin, that would pay for instrumenting all your bins.”

Many steel bins exceed 20,000 bushels these days and the street price of canola earlier this year was above $11 a bushel — do the math and you get Card’s point.

There’s another advantage to the system which often gets missed. That’s farm safety. Time was when you had to enter a grain bin to check the condition of the contents. People have been known to get trapped in the grain and either suffocated or crushed. The 3D system avoids that danger because you do not have to enter the bin to check the condition of the grain. The system tells you remotely if grain is at risk.

Managing grain so it does not go out of condition is the best way to avoid accidents such as grain entrapment, says Glen Blahey, agricultural safety and health specialist with the Canadian Agricultural Safety Association.

“Out-of-condition grain is one of the predominant reasons why people go into the bin,” says Blahey. “If, during the unloading process, someone goes in to deal with a clog, bridged grain or grain stuck to the side wall, the grain can collapse, engulf them and fatalities have been known to occur.”

Reprinted with the permission of Country Guide.