Anne Mahon, who’ll become the U of M’s 14th chancellor in June, sat down to talk in ARTlab on a pale winter afternoon. The volunteer job means seats on nine committees of the board of governors, a new set of black and gold robes, and handing out more than 5,500 U of M degrees and diplomas a year.

Mahon grew up less than five kilometres from the school’s main campus, and was the first in her family to go to university. She graduated with a bachelor of human ecology in 1987. Now, she’s an author whose books recount both the heartbreaking and hopeful oral histories of some of Winnipeg’s most marginalized—African refugees, former gang members and women who grew up in foster care.

Through dozens of interviews for her books in small apartments, in churches, and in the offices of social justice groups, Mahon says, she’s continually drawn back to the enormous value of a good education, and the opportunities it creates.

Anne, what was your experience like at the University of Manitoba?

The first thing I realized was I didn’t know how to write an essay. I came to university and I was not prepared, much to my own shock.

So, while everyone was eating pizza and drinking beer in University Centre, I would go up the elevator to some kind of program. It was in a little classroom. I remember feeling kind of humbled that I was there, but also that it was very necessary. I really did get what I needed.

I started out in the Faculty of Commerce and, in my second year, I realized I was missing the creative in my life. I had always felt good about the art I made. I sewed almost all my own clothes. And, in Human Ecology, there was the opportunity to do marketing of apparel and textiles as a major with a minor in business. The minute I was there, I felt like it was much more the right place for me.

It was partly a time of personal exploration and growth, but it was also a time of a lot of fun. I went to a lot of socials in MPR.

Did you have much to do with the U of M after you graduated?

No. I did quite a few different things. I went to work in the garment industry at Wescott Fashions and then at Olympic Pant and Sportswear and at Cotter Canada. I went to Ricki’s as a buyer. Then I had my daughter and I sold Casio watches two days a week. I had my second child, and my third.

I had the claim to fame of having landed the single largest order of Casio watches when I left the company. They called me from the head office and said, “What is this?” And I said, “I sold your product for you.” It was thousands and thousands of watches.

Sales is possibly something that can be in your blood and my dad was an in-the-blood salesman. I think I genetically inherited sales from my dad.

Then you moved to Ontario for three years.

It was challenging. I had had three kids in four years and I was living in a different city with them. That’s what made me start to think, ‛Okay, if I found this hard, what about an immigrant or refugee? Theyʼve got to find it infinitely harder than me.’

How did working on your books change how you view your own privilege?

I grew up in a modest, middle-class home where hard work was always instilled. I worked part-time through high school, as a babysitter, a camp counsellor and in a program at Eaton’s department store called Junior Executives. I paid for my own university tuition. But I also took many things for granted, like borrowing my parents’ car or having an easy time finding employment. I realize that being white, I have built-in privilege. I continue to learn from the participants in my books.

What kinds of stories have people shared with you?

I’ve heard most about overcoming trauma. Poverty. Isolation. Support.

In your own life, have you ever felt your resilience challenged?

When I was in Grade 5 I was bullied by a classmate. It brought lasting effects in school for a few years. And, residually, in my view of myself for a long time. I’ve thought about my interest in resilience quite a bit. I trace it back to that time. I have nowhere near the level of inner strength that the participants in my books have. But that bullying is the seed from which my fascination grew. Being bullied was a very difficult time in my life. But some good did come from it.

When did you get wind that you might be chancellor?

I got a call. I was just so surprised. I talked to my family first, of course. And, last, I talked to two people who work day in and day out for the disempowered in the community. Both of them I respect tremendously. And both said, “Oh my God, you have to do this.” The university is really a cornerstone of the city. And from my time spent with people in my books, particularly newcomers, I can see it through their eyes— they have an eye on opportunity and they have gratitude for higher education. And such respect for it.

I’m drawn to people who are on the fringe. I will be chancellor for all but my heart tends to be with people who are more in the nooks and crannies of the university. Sometimes people on the fringe don’t feel welcomed or encouraged. Sometimes people in the very centre don’t either. We all want to feel welcomed and we all want to feel encouraged.

I volunteer in the jail with women. I am going there tonight. I have sat down with former gang members. I have the tremendous and unusual privilege in my life of having been with a very broad spectrum of people. So the connecting part of the job should come fairly naturally, and the welcoming and encouraging are on my radar.

I wouldn’t have been asked to be chancellor if I hadn’t written the books. And I wrote the books because people who didn’t know me, who live in the margins, trusted me.

Having been invited to this role, I come on the shoulders of the disempowered who have been so good to me. There is a lot of poverty in Winnipeg. We have one of the highest child poverty rates and somehow the message of university and opening doors needs to go to them too.

When new graduates come across the stage at the University of Manitoba convocation ceremonies, they will increasingly be from all over the world. What will you be thinking about?

First and foremost, behind every face is a story. Sometimes we assume we know the story, which is a mistake, and sometimes we just have no clue. Most of us want the same things. It doesn’t matter what we look like or where we have come from. We want love. We want to feel belonging. We want opportunity, whether that’s for a decent job or so we can give our kids what we think our kids need. We want to have peace inside ourselves and peace in our communities.

I’ve learned two things writing these books. One of them is not to judge anybody. Nobody. We live in a fast world where we want answers and our egos want to think we know this or that, but we really don’t. And the other thing is, and it sounds kind of clichéd, but, wow, have I learned gratitude.

And even my friends who are former refugees who are doing really well—they’ve learned English, and their kids are young, and they have a hybrid culture between Canada and their birth culture—still, they work so hard. They don’t take anything for granted. And that challenges me.

I’m looking forward to standing on the dais and looking out at everybody. I’m such an observer of people and I want to see what that looks like. All the different ages and colours, and all the stories that are behind all those faces. I am looking forward to that moment very much.

You talked to Harvey Secter [BComm/67, LLB/92], who’s been chancellor since 2009, before you decided to step into the role. What did he tell you?

I talked to Harvey for an hour at a coffee shop and I found him very warm and gracious, and very encouraging. I appreciated that. He talked about being a bridge from the university to the community and back to the university.

And he gave me two pieces of advice: The first was, “Just be yourself, don’t try to be anyone else.” The second was, “There are no rules for how to do this job.”

He also said he bought new shoes before the first set of convocations. And he told me: “Don’t wear brand-new shoes.”

How significant is it that you are a woman in this job?

In 142 years, there has been one female chancellor. So I think the university made the right choice to select a woman, but I tend not to look at things through a gender lens. While I value balanced representation and feel it is critical, my priority is working with people of heart; people who are courageous, care for all, are open and generous.

My original plan for early June, when I will be installed, was to be in Vancouver at the world’s largest women’s conference, Women Deliver. I have a ton of friends who will be going. It’s not escaped me that the reason I won’t be there this year is because I will be conferring degrees.

Maybe I will say, “I am not there. I am here. And I am delivering because I am a woman.”

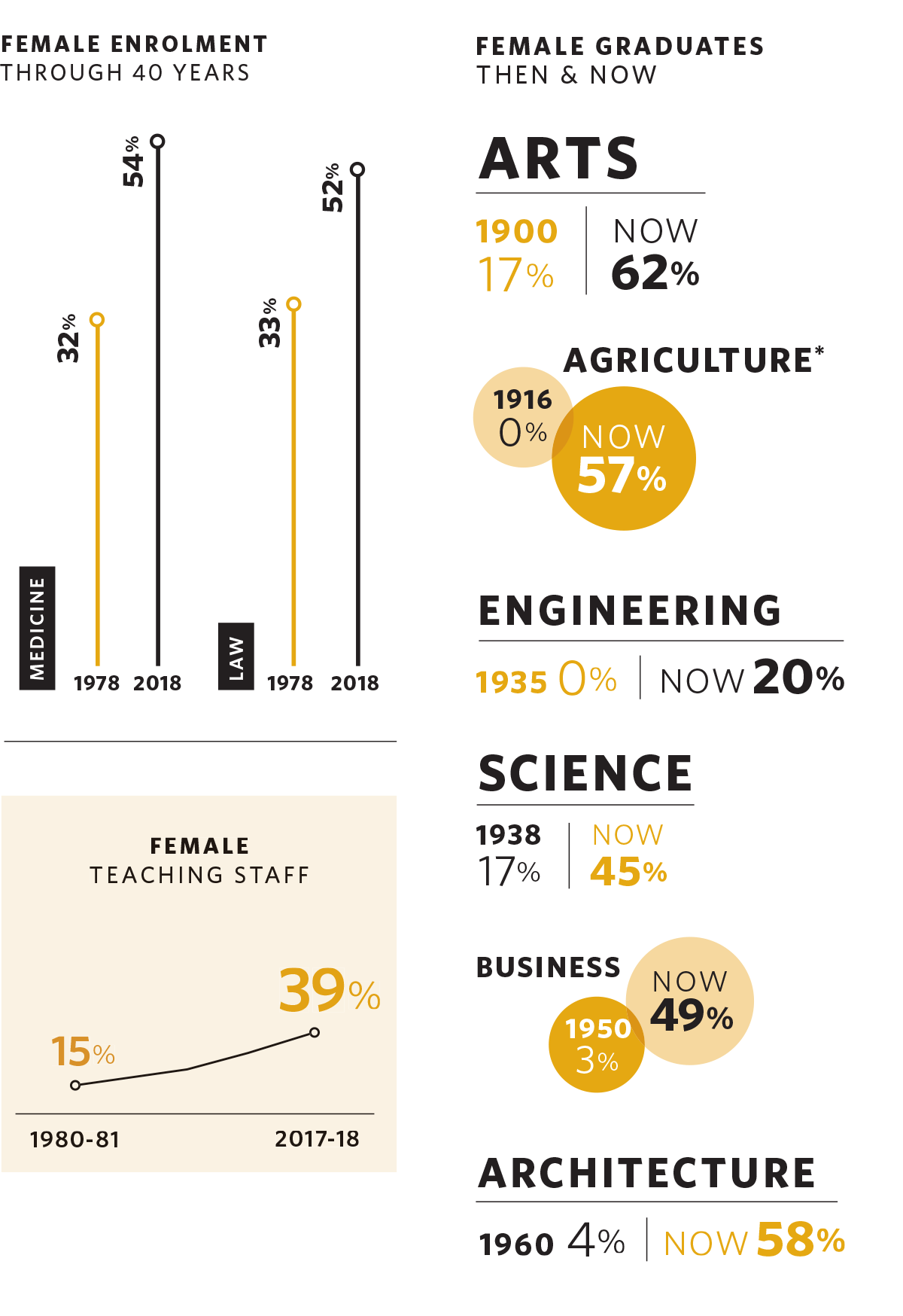

TIMELINE

Anne Mahon is the second woman since 1887 to be chancellor of the University of Manitoba. It got us thinking how the numbers have shifted over time—and where do we need to go next?

When the department of human nutritional sciences moved from the Faculty of Human Ecology to the Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences in 2014, it further boosted female representation.

**Statistics provided by the Office of Institutional Analysis are the most recent available (2017).

AMPLIFYING VOICES

Mahon’s book, The Lucky Ones: African Refugees’ Stories of Extraordinary Courage, is a collection of first-person accounts from newcomers. Among them: Sally Wai [BSW/09], a refugee from Sierra Leone who went on to earn a social work degree from the University of Manitoba and now works at the Community Education Development Association in Winnipeg.

“The first time I met Sally,” says Mahon, “I came with a guest as a last-minute tag-along to a community lunch she was hosting. But she welcomed us in as she would a good friend. She said it is the African way to welcome extra people. Her big-heartedness proved itself again the day I asked her if she had any suggestions for individuals who could be interviewed for [my] book. She offered herself. A woman who is constantly giving, she was the first person to offer her story.”

Here are some excerpts:

I arrived with very little and there were many of us: my daughter and me as well as my elderly mom and three of her other grandchildren. When we first arrived, I quickly found a church to attend. It was difficult for me, but I stood up in church and said, “I have come to Canada and I have nothing.” Initially it was hard for me to ask because it is not a custom in my culture to ask for assistance. I was honest because I needed the help.

I came to Canada because I had been living surrounded by war and had seen the suffering up close. My mother, then in her late sixties, had to hide in the rural bush of Sierra Leone for two months to protect her three young grandchildren. Our country was not safe. We had family members die, and so we decided to get out. That was 2002.

Today, I am part of a community, one I am proud to say many of us have built together—the Central Park neighbourhood. Sure, there are drug dealers and crime here, but there are many strengths too. People here open their doors and their hearts to each other. That is the way to survive as a newcomer.

Where I come from, women don’t have rights: they can’t speak out or make political decisions. They don’t even have the ultimate right to their own bodies, so if they are abused or raped there is no way for them to seek help or justice. It is only now that women in Africa are fighting for their rights and to be able to have representation in decision making. That is very new in our society. Women need help to know what their rights are. If a woman is abused, here in Canada you dial 911, but that service does not exist in Africa. There is no point in going to the police there, for who are the police? Men. There lies the bias, and this bias is part of the system already.

Every day my office doors are open. We’ve started a sewing co-operative, a conversational English group, and we are gardening on land given to us by the University of Manitoba. On Fridays, we take turns cooking our native foods for each other because we are a diverse group: Somali, Ethiopian, Korean, Sierra Leonean, Sudanese, Liberian, Filipino, Aboriginal, Nigerian, South American and Chilean.

I have had to work two and three jobs just to go to school. Newcomers whose education is not accepted in Canada have a hard time. They take on menial jobs to pay for their re-education because with no valid education they can easily go down the drain. It is difficult to advance.

When I was young, I lived with my aunties. They beat me and told me I was good for nothing. I felt so low I tuned my mind to accept the beatings; it was part of my daily life. But the only thing I never accepted was that I was good for nothing and couldn’t do anything with my life. I said to myself, I will take these beatings, but I will do something with my life, and I will impart this message to other women. I will stand for the truth, for what I believe in, and not accept what these other people are telling me.

I plan to take this message back to Sierra Leone. My hope is that, in 10 years, I will have a resource centre there. It will be for every woman and girl-child of Sierra Leone. I have a special place in my heart for these less fortunate girls. They are young and not in school. Often they have no parents, having been orphaned by war or AIDS. They are in need and have no way to cope. I want to teach them they can rise above the abuse and the suffering; they can find their voice and become strong. I want to empower women and the girl-child to give them hope in society. I want to help women know how to live their lives independent of men.

It is most humbling to read Sally Wai’s account of her life. Inspiring as well. I am grateful for those who have dedicated their attention and thoughtful applications to helping people who have sought refuge in Canada. I would like to be a helper in the lifelong commitment to bettering the lives of those living living with inequities.

“Beautifully written article on an outstanding woman”

https://news.umanitoba.ca/embracing-leadership/