When toy giant Mattel launched their revamped line of Barbie dolls earlier this year—with their more realistic body shapes and sizes—the world responded with a collective ‘Finally!’

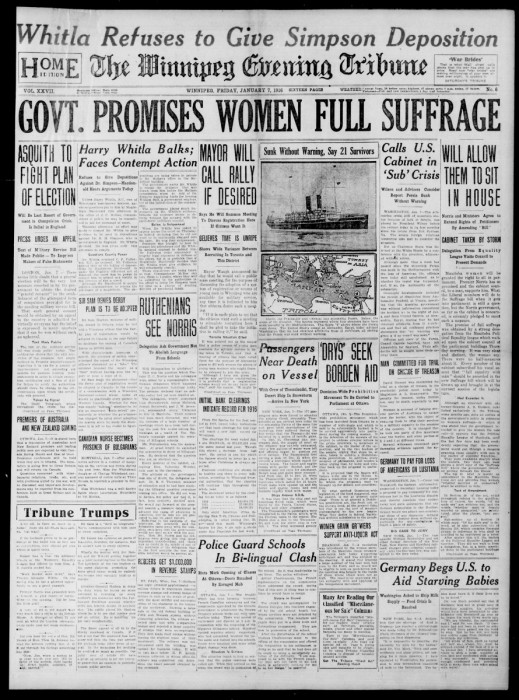

Coincidentally, the new dolls were announced on the 100th anniversary of suffragist Nellie McClung’s historic win allowing many Manitoban women—but not all—the right to vote. (See sidebar, page 20.) It’s easy to imagine the suffragists of yesterday pointing out the absurdity: A century ago we achieved equal say in the leadership of a province, and only now are we removing a doll’s corset, allowing a women’s real shape to be seen and celebrated.

A local hero, McClung pushed open a heavy door for gender equality in 1916. In the decades that followed, we’ve witnessed big steps forward for women in business, entertainment, politics and education—but equality eludes us. Today, women steer multinational companies—but there are still far fewer women than men in executive roles or sitting on corporate boards. Women make millions at the box office—yet still millions less than their male co-stars. And they lead major scientific discoveries—yet still we require outreach programs to convince girls they’re smart enough to pursue math.

In 2016, the barriers to achieving equality among the sexes are less tangible and more deeply rooted. Some are created and nurtured by women themselves. The solutions may be complex but the benefits— from a stronger economy to a more just society for everyone—are as compelling today as they were 100 years ago.

In fact, recent studies by the World Economic Forum and the McKinsey Global Institute show that closing the gender gap in the workforce would have a tremendous impact for a global economy in which growth has been stalled for almost a decade. According to McKinsey “as much as $28 trillion—or 26 per cent—could be added to global annual GDP by 2025.”

We wondered: What would McClung do today to achieve equality? We explored the answer through the stories of several U of M alumnae who have done their part in heaving the door open wider—for themselves and for others.

GRIT AND COMMUNITY

Jessie Lang [BA/37, BSW/63] didn’t shy away from pursuing a degree in mathematics—even though it was the 1930s. The 99-year-old says she was unfazed about being one of the few women to study math at the time. Born two months after Manitoban women got voting rights, Lang is about to mark her 100th birthday with a century of memories. She lost everything in the Red River flood of 1950 when water rose to the second-floor windows of her Winnipeg home. She was a passenger on one of the trains that crashed head-on in Dugald, Man., in 1947, killing 31 people. She endured the Great Depression.

And she was a parent to two daughters during an era that discouraged mothers from working outside the home. Volunteerism was her job—and she broke barriers. As the first woman to chair the board of the Health Sciences Centre, she helped open a daycare for the children of female employees so they could continue to work.

“I think it’s sort of instinctive that she pushed the boundaries without even thinking about it,” says Lang’s daughter, Signy Hansen [BPE/67].

When Lang was widowed at age 44 she went back to school, pursuing a social work degree at the U of M before becoming a guidance counsellor. After losing a daughter to complications from multiple sclerosis, Lang dedicated herself to raising money to find a cure. Lang has the grit to break through barriers but credits the power of community for real change. She believes the more involvement women have within the community, the more they crush gender inequality.

“I just think [it’s important for progress] to keep on participating in society and in the things we are doing—more and more,” she says. In the 1960s, she was part of an all-female investment club, giving women a vehicle to learn about stocks and bonds. She was also a member of a group that brought women together to write and present academic papers—and at one point was president of the groundbreaking club.

Gutsy women like Lang and Mc- Clung have been role models for all who fuel the ongoing drive toward equality in the 21st century.

Still, equality eludes us. Canadian women earn 82 cents for every dollar men earn, according to Catalyst Canada, a non-profit organization focused on progress for women and workplace inclusion. The annual pay gap of about $8,000 is double the global average. And it begins out of university where the gap sits at nearly 7 per cent.

“On key issues like pay equity the barometer has barely moved at all in the last 30 years,” says Karen Busby [JD/81], Faculty of Law professor at the U of M. “The barometer is not moving very fast. I don’t know [what the solution is]. I don’t have a simple answer.”

THE BARRIERS WOMEN NURTURE

Emterra Group CEO and founder Emmie Leung [BComm(Hons)/76] came to Winnipeg from Hong Kong in 1972, intent on pursuing a university degree despite her father’s insistence she didn’t need a post-secondary education. He told her she should focus on a different goal: being a housewife and mother.

Defiant and determined, Leung struck out on her own. She worked two waitressing jobs to pay her way in a new country, surviving off rice and Cheese Whiz. After getting a business degree from the U of M in 1976, Leung hatched a start-up to collect and sell recyclables overseas, decades before sustainability was on anyone’s mind. She got the idea after seeing stacks of newspapers piled up on a street curb alongside garbage bins.

Emterra is now a $100 million family of companies—with more female vice-presidents than men despite waste management being “a very macho industry,” Leung notes. In the last decade she has seen a jump in the number of women getting into the environmental business and she’s hopeful it’s just the beginning.

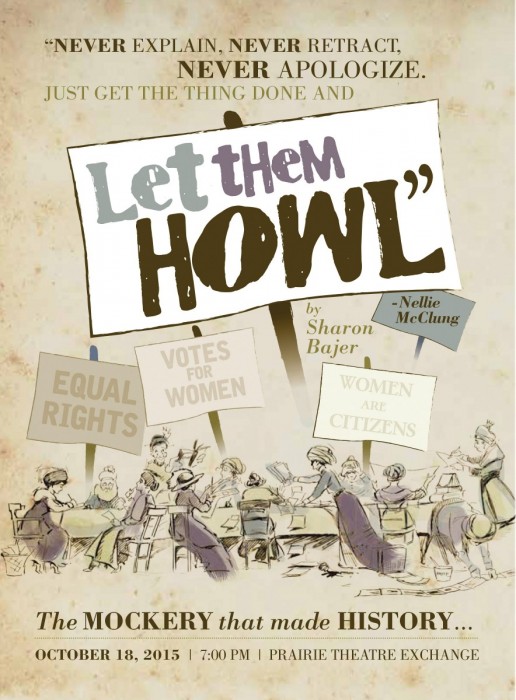

// IMAGES PROVIDED BY THE NELLIE MCCLUNG FOUNDATION

// IMAGES PROVIDED BY THE NELLIE MCCLUNG FOUNDATION

It’s tough since sometimes the barriers women face are barriers they’ve created, Leung says. “You’re torn between your two loves. As a mother you want to be with the children, right? So you have a gap in your career or some of them may even take a step back. So it has a lot to do with the culture and at the same time the society, whether it be the ladies getting the opportunity or the ladies themselves—whether they are determined to take that opportunity.”

Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook’s chief operating officer, insists in her 2013 bestselling book Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead women should ask their partners to do at least half the parenting work. She puts the onus for progress—and maybe even the blame for a lack thereof—on women, noting we need to “dismantle the hurdles in ourselves.”

“Don’t let anybody tell you, ‘You can’t do that.’”

Michelle Carriere

“We hold ourselves back in ways both big and small, by lacking self-confidence, by not raising our hands, and by pulling back when we should be leaning in,” Sandberg writes.

“We internalize the negative messages we get throughout our lives, the messages that say it’s wrong to be outspoken, aggressive, more powerful than men. We lower our own expectations of what we can achieve.”

Leung says she feels people at first can underestimate her business savvy because she’s female and because she’s an immigrant. The fivefoot- one entrepreneur believes there is a greater expectation for women to “contribute in the equation of the relationship”—to prove their worth rather than it be a given.

“They don’t expect us to do big things,” says Leung.

Nor, it seems, do businesses expect to pay women big dollars.

Sandberg suggests women negotiate like men. Only on the insistence of her husband did she counter Mark Zuckerberg’s original offer and she landed a more lucrative deal.

BEING A PIONEER CAN BE LONELY

Like Leung, Shelley Hart [ExtEd/93/94/02] knows a thing or two about thriving in a macho environment.

She could feel the double-takes as she stepped out of the police cruiser during her first shift in Winnipeg’s North End—on Christmas Eve, 1978. The second glances were so intense the word “whiplash” comes to mind, she says.

The former deputy police chief of the Winnipeg Police Service says she knew she was a rare sighting in a high–crime neighbourhood not accustomed to seeing female police officers. Hart, at 20, and another colleague from her graduating class were the first women to be assigned there. In fact, it was the last district in the city to open up to female officers.

“It was a bit like being an exhibit at the zoo,” Hart says. She knew not everyone believed she could handle the job. “Even though you’re the one taking the report and asking questions, the people don’t talk to you, they talk to your male partner,” she says. “I was an anomaly—there was no question. It was new ground.” Being a pioneer can be lonely. For many women who are first in fields dominated by men, female colleagues are few and far between. And without role models to step up and lead the way, progress would stagnate. Hart admits as a young recruit she didn’t even think a promotion beyond constable was possible for women in the Winnipeg Police Service.

“I never thought of becoming the chief. It wasn’t even in my wildest dreams but I’m sure every guy sitting in that recruit class was thinking ‘One day…’” Hart says.

Her perspective changed when a female co-worker became a patrol sergeant. “It was that moment where you go, ‘That’s possible.’” The University of Manitoba alumna moved through the ranks, eventually becoming the first female inspector in the Service’s elite homicide unit and by the time she retired in 2014, deputy police chief. Hart was the first woman to hold the post.

She attributes her success to an unlikely source: Men. Men are the key to creating greater gender equality in the workplace, Hart says.

“I would not have been successful without the mentorship of some fabulous men. I think that often goes unstated,” says Hart, who got into politics after her retirement and is now mayor of the Rural Municipality of East St. Paul. “We had some really progressive men who did not accept the status quo.”

McClung too had strong support from men during her plight, including journalists, politicians and labour leaders. A recent study in the United Kingdom made a surprising discovery: More men support gender equality than women (86 per cent compared to 80 per cent). The Fawcett Society, a charity that promotes women’s rights, found the majority of the men they surveyed believed greater equality would benefit the economy.

So, are men the solution or the problem?

“CALLING ALL WHITE MEN…”

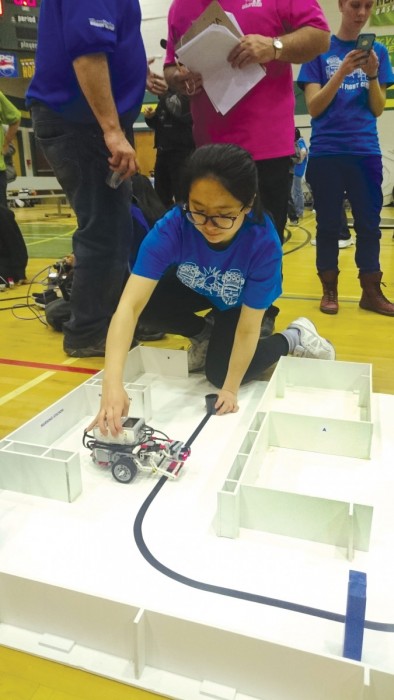

// WISE KID-NETIC PHOTO SUPPLIED BY WISE KID-NETIC ENERGY

Companies need to start seeing men as part of the solution, insists Catalyst Canada. In their 2012 study Calling All White Men: Can Training Help Create Inclusive Workplaces? they tracked a leadership development program led by mostly white men at a multi-billion-dollar company and discovered it had a transformative effect. They noted participants became “significantly more accepting of the notion of white male privilege” and took greater responsibility to be inclusive. If these individuals are the ones doing the hiring and promoting, could women then secure more top positions? A global comparison of management gender (also by Catalyst Canada) revealed that as recently as three years ago, women held only 27 per cent of senior management positions in Canada. China had the most, with 51 per cent.

Could quotas be the answer? U of M political studies professor Andrea Rounce describes Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s genderbalanced cabinet—the first in Canada’s history—as “a good first step.” His explanation “Because it’s 2015” made headlines beyond our borders, reminding us that equality is still a rarity around the world, even in 2015.

Canada comes in 49th in the Inter-Parliamentary Union’s global ranking of countries based on their percentage of female representatives in elected parliament. “Even though we have gender parity in cabinet, only 26 per cent of our parliament is women,” notes Rounce, who doesn’t think we’ll get to 50 per cent within the next 30 or 40 years. “This is not an easy project,” she says.

While critics were irked, the most powerful portfolios—like treasury board and finance—went to men, Rounce points out that Ontario’s Catherine McKenna was assigned a portfolio with comparable esteem: environment and climate change. Protecting the planet got a lot of play in Trudeau’s campaign, which happened to be led by a woman. In fact, women were chosen to run the campaigns of all three of the main political parties—another first in Canadian politics.

University of Calgary political science professor Brenda O’Neill says there’s an expectation that female politicians need to prove they’re better than men to be considered as good as men. O’Neill was one of the academics who spoke at a noon-hour roundtable at the U of M 100 years to the day that the suffragists got the vote in Manitoba.

Setting quantitative goals is just part of the answer. While women are often involved behind the scenes not as many are choosing to run themselves, for a variety of reasons, says Rounce.

They’re less likely to have political connections or see themselves as the political type, research shows. They’re also more likely to be juggling childcare and the care of elderly family members. Workplaces that accommodate these “systematic challenges” will help move along change, Rounce says.

McClung would likely applaud systemic changes but if we really want to ramp up the rate at which women and men achieve economic and social parity, we need to start much earlier, with girls in middle and high school—before they set limits on what they can do and achieve.

STEM: THE FINAL FRONTIER

It’s too bad Instagram posts from the much-followed Kardashian sisters don’t go beyond their glamorous lifestyles, jokes Michelle Carriere. “If they were more into science and engineering then more girls would be,” says the 26-year-old.

She knows social media holds a certain power—so too does a cool robot. Two years into her engineering degree at the U of M, Carriere leads the All-girls’ Robot Fight Club for Grade 7 to 12 students through the faculty’s outreach program WISE Kid-Netic Energy. She introduces girls to computer programming through robots and hopes they’ll get excited about pursuing a field traditionally favoured by boys. To compete in the upcoming Manitoba Robot Games, the club’s eight participants are programming their tabletop Lego robots to navigate an obstacle course. Carriere also helped out with an all-girls’ code-makers camp and brings hands-on science experiments to Indigenous communities.

She’s trying to reverse the misconception she continues to see among high-school girls: Science and math aren’t cool, and they’re more for boys. “It’s just like this social stigma,” she explains. At 12, Carriere was already modifying her bicycle, improving the tension on the brake line, switching out the pads. Her dad, an electrician, always encouraged her to tinker with his tools in their garage. By Grade 10, Carriere was okay with being the only girl in her power mechanics class. A former participant of an outreach program herself, she tells girls: “Don’t let anything or anybody tell you ‘You can’t do that’. Try it out.” We have witnessed significant progress in the success of women in the education system in North America. Across university disciplines as a whole, women outnumber men in undergrad studies. But this levels off by the doctoral level and from then on men outnumber women at every academic rank. In the physical sciences, computer science, engineering, and mathematics—females account for 24 per cent of students Canadawide, a study by the Council of Canadian Academies found.

In 2008, the Council launched an investigation when the first Canada Excellence Research Chairs were announced and there wasn’t a single woman among the 19 recipients. These chair-holders and their universities receive up to $10 million each to focus on priority areas of the federal government’s science and technology strategy. The lack of women drew public outcry. The study identified typical factors stopping women, from stereotyping that defines social roles to research environments “chilly” toward women.

A CENTURY IN THE MAKING

You can easily imagine McClung and her suffragist sisters sighing sadly and then raising their pickets on university campuses across Canada. Get involved, they’d likely say. Jessie Lang agrees. Positive change begins by sharing your voice in the community.

Has a man ever told her she couldn’t do something?

“Not that I can remember,” says Lang, who once played defence for the university hockey team.

“I think he’d be afraid to,” jokes her daughter. “I don’t think a man would dare say that to you.”

Lang says she has no regrets.

Barbie-maker Mattel, on the other hand, might have a few.

They only released a curvy, petite and tall Barbie to represent real body types once sales had slumped for eight straight quarters.

“We believe we have a responsibility to girls and parents to reflect a broader view of beauty,” Evelyn Mazzocco, senior vice president at Mattel, said in a press release.

But it seems many girls might have already moved on. The drop in sales was widely attributed to girls preferring electronic gadgets.

Perhaps that would make Nellie McClung smile.